There is still time for South Australian state officials (both forensic and legal) to ‘come clean’ about past failures and fulfil their duty of disclosure to the court regarding former forensic pathologist Dr Colin Manock, says DR BOB MOLES in his review of Drew Rooke’s book.

A Witness of Fact will prove to be one of the most significant books in the genre of wrongful convictions analysis. Many of the basic facts which are at the core of this study have been publicly available for over twenty years. The circumstances giving rise to them occurred in the thirty or so years prior to that. There have been a substantial number of television and radio programs and print articles about these issues. I (with joint authors) have written four books and a good many academic and media articles about them – so why the need for another book?

This is the problem I had to address when I first met Drew after he had published his previous book One Last Spin. In reading that book about the pernicious effect poker machines had on some of the most vulnerable people in our community, I knew that Drew had the capacity to engage with some of the most powerful people who had created the problem (along with the considerable profits they generated) and the weak and vulnerable who had been exploited by them. I wanted to see if he would use his undoubted skills to address this issue which we had been struggling with for the previous twenty years.

State pathologist never qualified

We had identified a person (Dr Manock) who had been the chief forensic pathologist in South Australia for some 27 years. He had conducted over 10,000 autopsies and helped to secure over 400 convictions. The major problem, we discovered, was that he was never qualified to do this work or to appear as an expert witness in court.

However, as academic lawyers who had worked with practicing lawyers and forensic specialists over the years, we could only go so far with our analysis. What we needed was a skilled researcher, not previously involved with these issues, preferably from interstate, who could approach the key players involved in order to ascertain their understanding of what had occurred.

On the face of it a potentially daunting task. Manock had in years past been rather notorious in litigating when things displeased him and in more recent years, had launched defamation proceedings against those he perceived to be his adversaries. This included one against myself, which ultimately proved to be unsuccessful, thanks to the extensive efforts of Graham Archer and Channel 7 Today Tonight for which he was the executive producer.

Thankfully, Drew was up to the challenge, and with the support of his publisher, a modest grant and our network of contacts, he set about the substantial task of piecing the story together before he could commence his further original research.

This has involved interviewing some of the leading forensic specialists, from Australia and overseas, who had been involved with Manock’s cases over the years and finding out what they knew about him. It appears that none of them were aware of the fact that he was actually unqualified to do the work or to give evidence about it in court. It seems that it never occurred to them that the state would be using someone in such a senior position, to undertake such sensitive and important work, whilst knowing that he was not qualified to do the job.

It never occurred to them that the state would know that he was just handed a certificate stating that he was a Fellow of the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia, without his having done the five years of arduous study, and which they as senior pathologists all had to complete to get their qualifications.

The senior lawyers who had to engage with Manock in the numerous legal cases were, it seems, equally in the dark. They too had worked on the not unreasonable assumption that the forensic services and prosecutors would abide by their legal duty of disclosure and inform them of any issue which might undermine the credibility of their chief forensic witness. After all, the senior officials in the forensic science centre knew that Manock was not qualified, because they had given sworn evidence to that effect in their litigation with Manock in the mid-1970s. The State of South Australia knew about it because they were a party to that action, and the forensic services operated under the jurisdiction of the Attorney-General. Prosecutors, as representatives of the state, are always taken to know what the state itself knows.

Manock’s propensity to ‘adjust the facts’

Drew also noted that the forensic services should have known about Manock’s propensity to ‘adjust the facts’ to suit his convenience merely by perusing the job applications he submitted to them. In the first one he said that he had completed 1,200 autopsies whilst in England before coming to Australia. In the next application he said he had completed 1,400 autopsies there, and in the following one it went up to over 1,800. In later court proceedings he boosted it to ‘between 2,200 and 2,300.

As to his prior experience, Drew also points out that Manock whilst a lecturer at Leeds University had taught, and no doubt had close contact with, the young Harold Shipman who it seems had a special interest in forensic pathology issues. Shipman was later found to have killed over 230 of his elderly patients.

Later, in his own career, Manock had engaged in his own form of ghastly misconduct in addition to misleading the court as to his qualifications, skills and forensic findings in individual cases. He had dissected the body of an aboriginal man in an outback town, in front of a crowd of the local people, apparently as a form of entertainment. Drew, with his customary sensitivity, is able to convey the shocking aspects of this event, and its impact on those involved, just as he does in discussing other cases in which Manock had dealt with deceased aboriginal people in a manner which can only be described as insensitive and unprofessional.

Drew discusses the case of Derek Bromley, also an aboriginal man, which will prove to be one of the most important for the Australian legal system as it still remains unresolved after he continues to serve more than 38 years in prison. In this case, as in many others, there are an impressive array of forensic specialists who provided sworn evidence to the effect that Manock’s forensic work and his findings were incomplete and not based upon sound scientific principles. In the earlier case of Emily Perry, Drew points out that the High Court of Australia found that Manock’s evidence was ‘not fit to be taken into consideration’, and in the case of Henry Keogh it was found to be ‘false and misleading’.

As Drew explains, even to this day, the legal officials in South Australia are still trying to hold back the tide of common sense. His approach to the Attorney-General was met with the response by some official that the AG could not respond to his inquiry (about Manock) because it concerns matters which occurred before the AG took office. If that were a principle to be generally applied, the Prime Minister of Australia could have been excused his apology to the aboriginal people for the hurt and distress which had been caused to them many decades ago, and the inquiry into the institutional abuse of children would never have occurred. People who hold high office are responsible (as office holders) for all prior misconduct for which ‘that office’ is and has been responsible for – and one might have thought that the Attorney-General and her officials would have known that.

The other explanation apparently given by the official was that the matters which Drew wanted to discuss might be the subject of ‘legal proceedings’, and therefore not suitable for discussion by the Attorney-General.

Successive Attorney-Generals’ failures

It will come as no surprise to people in the community that the AG is the senior law officer of the state, and presumably, in that capacity will find that most of the issues which the AG has to address will involve legal proceedings of one sort or another. In this case, the suggestion is that the ‘legal proceedings’ concern around 400 wrongful convictions and at least 10,000 potentially unlawful autopsies. It also involves the forensic services, the office of public prosecutions, the judiciary (for all of whom the AG is ultimately responsible) and a wide range of other lawyers and officials who knew or ought to have known about Manock’s failings and failed to disclose them in legal proceedings spanning more than 53 years.

The failure of successive AGs to address these issues will rank alongside the similar failures of senior officials in churches and other major institutions (including banks and insurance companies) who failed to respond in a timely manner to allegations of fraud and corruption.

The timing of the publication of Drew’s book is most fortuitous. There are, as the AG’s official pointed out, ongoing legal proceedings. However, there is still time for the state officials (both forensic and legal) to ‘come clean’ about the past failures and fulfill their duty of disclosure to the court. Certainly, a number of the senior forensic and legal officials interviewed by Drew have told him that a review will have to occur at some stage, and that the issue will never go away until it is reviewed and resolved. Even the head of the SA forensic services appears to have admitted that the constant references to past misdeeds cuts across their attempts to inform the public of recent successes and progress being made in this exciting and challenging field.

It would be ironic and distressing to find that the highest courts in the land have to continue to deal with these matters in apparent ignorance of important facts which will now be known and understood by the wider community, both in Australia and overseas, as a result of this important review by Drew Rooke, for which he is to be congratulated.

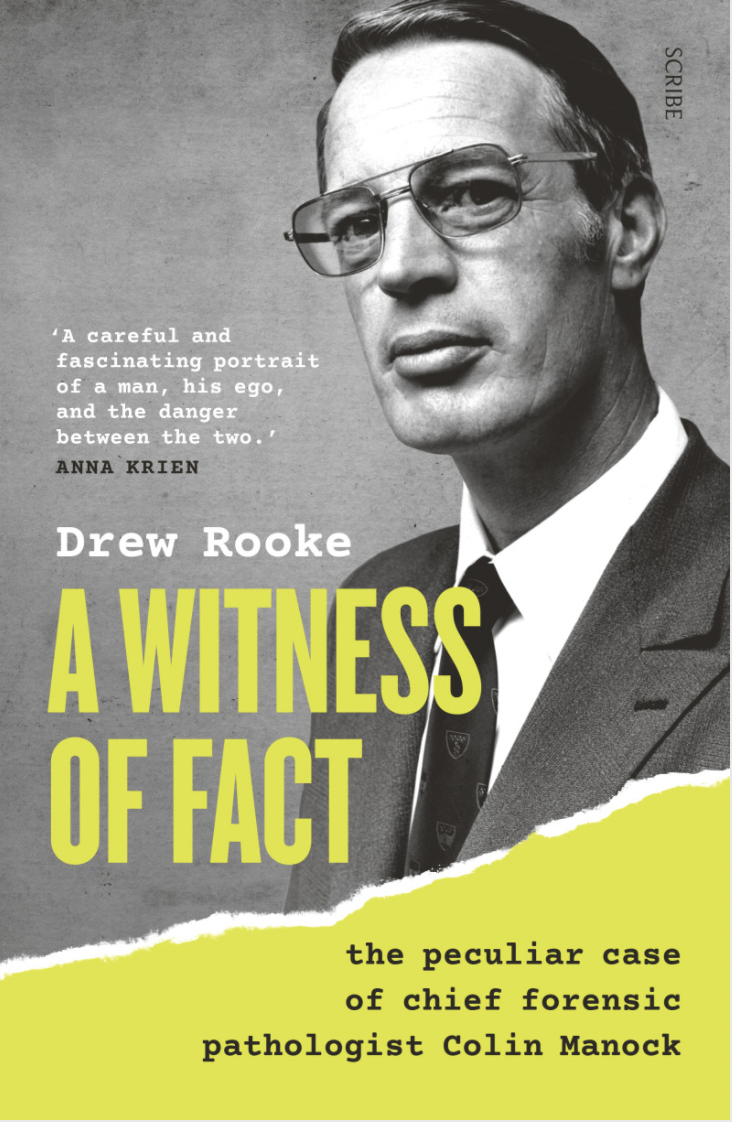

A Witness of Fact: the peculiar case of chief forensic pathologist Colin Manock

A Witness of Fact: the peculiar case of chief forensic pathologist Colin Manock

Drew Rooke – Scribe publishers

ISBN 978 19223 10057 – RRP $32.99 – Category Nonfiction

Also available as an e-book on Amazon Kindle and Apple i-books.

Released February 2022

Horrifying behaviour on the part of Manock. Never mind those in power who kept him in that position for so many years, despite having full knowledge of his inadequate qualifications, and of wrongful convictions. Each time I have a specialist doctor who has not done the complainant examination but instead a substitute, who invariably has lesser qualifications, called to testify by the prosecution, I object. In a few cases now I have cited the appalling Manock years in SA as part of my reasons for objection and the swathe of convictions involving his alleged “expertise” that will undoubtedly come before the courts on appeal in the future. The mention of his name and the issues arising from his lengthy period of conducting PMs as an unqualified pathologist has never been responded to by the court. The sooner that there is a proper review/ acknowledgment of the SA failings the better.

Thank goodness for people like you and Drew for having the guts to blow the whistle and the determination to continue to apply pressure to decision makers who could/should/must deal with it.

My experience with senior government positions is that once they get their bum on the seat others forget exactly what the background of these people actually is. A common characteristic of some I have known is that they are often narcissistic bullies.