Andrew L. Urban.

Consistency in the administration of the law is absolutely paramount – yet compensation for mistakes (or malpractice) that convict the innocent is applied higgledy-piggledy by politicians throughout Australia.

Compensation is where politics and the law collide. It is not the courts that make decisions on compensation for wrongful convictions: it’s politicians. Those seeking compensation for their misfortune at the hands of the law often find the misfortune just continues at the hands of politicians. There are no rules, there is no consistency across jurisdictions (or even within jurisdictions) and society has not developed a rationale on which to build agreement. It’s just as much a part of delivering justice as due process and a fair trial.

- In February 2018, a $2.5 million ex-gratia payment was made to Henry Keogh by the South Australian Government after his successful (final) appeal against his murder conviction; he had spent almost 20 years in jail.

- In November 2015 Roseanne Beckett was awarded damages after a lengthy court battle against the state of NSW over compensation for malicious prosecution. The $4,091,717 awarded increased from $2.3 million awarded in August because of interest. Beckett was arrested on August 24, 1989; she was released in 2001 after serving 10 years of a 12-year sentence, after being wrongfully jailed for soliciting two men to murder her husband.

- In April 2003, the Western Australian Government approved a $460,000 ex gratia payment to John Button who was convicted of manslaughter in May, 1963. He was sentenced to 10 years’ jail, and served 5 years before being released on parole in December, 1967. His conviction was overturned at appeal in 2002.

- In December 2016 a couple (Catherine Atoms and Robert Cunningham) tasered & detained by police in Fremantle eight years earlier were awarded more than $1.1 million in damages. (See below)

- In 1992, the Australian Government paid Lindy Chamberlain an ex gratia payment of $1.3 million, as well as $396,000 for legal costs and $19,000 for the family car which had been effectively destroyed as a result of forensic investigations. She had been in jail for 3 years for the murder of her daughter Azaria. The dingo did it …

- In 1979, Tim Anderson, Ross Dunn and Paul Alister were convicted in New South Wales of conspiracy to murder and sentenced to 16 years in prison. After serving seven years, they were unconditionally pardoned and were each awarded a $100,000 ex gratia

- In 1980, Douglas Rendell was convicted of murdering his wife in New South Wales and after serving eight years in jail, was awarded a $100,000 ex gratia payment.

The Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) published a paper in 2008 which found that “Australian states and territories can make discretionary ex gratia payments, although determination of compensation amounts is unclear. Compensation levels for wrongful conviction in Australia are not as generous as tortious claims. The current system of ex gratia payments that exists in all Australian jurisdictions (other than the Australian Capital Territory) is arbitrary. The introduction of dedicated legislation or specific guidelines for wrongful conviction would help bring these Australian jurisdictions into line with international human rights best practice.”

Arbitrariness abounds in this sphere: compare the following payouts with those above (eg $20,000 for a few hours, v $100,000 for eight years). “False imprisonment cases (not to be confused with wrongful conviction) are quite uncommon, so it is difficult to arrive at a clear tariff for the tort, but the following cases give an idea of the level of damages ordered:

- A protestor in Queensland who was refused entry into a sitting of Parliament and wrongfully removed and imprisoned by police for a matter of hours was awarded $20,000 plus interest. The judge found that the plaintiff had suffered little or no shame, indignity and mental suffering but nevertheless had had his rights violated (Coleman v Watson [2007] QSC 343, BC200709939).

- A NSW man who was wrongfully arrested and imprisoned by police for 56 days pursuant to an ultra vires order of a magistrate (for failing to pay costs of an earlier unsuccessful prosecution) was awarded $75,000 plus interest (Spautz v Butterworth (1996) 41 NSWLR 1).

- A NSW man attended a police station for an interview and was arrested, charged and detained for three hours in relation to a number of separate matters. It later transpired there were no reasonable grounds for the arrest. The man was awarded $25,000 plus interest (Zaravinos v NSW (2005) 214 ALR 234).

The AIC report concludes that “It would be appropriate for compensation for wrongful conviction to be calculated in a similar manner to damages for false imprisonment. It would also be desirable for the criteria upon which these decisions are based to be publicly available, and that reasons be given for any such decision.

“It would be preferable for each Australian state and territory to either implement legislation akin to the Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT) or draft specific guidelines for the award of compensation to wrongfully convicted people (akin to those used in New Zealand). Victoria recently introduced its own human rights legislation, which did not include such a provision.”

Section 23 of the Human Rights Act 2004:

(1) This section applies if—

(a) Anyone is convicted by a final decision of a criminal offence; and

(b) The person suffers punishment because of the conviction; and

(c) The conviction is reversed, or he or she is pardoned, on the ground that a new or newly discovered fact shows conclusively that there has been a miscarriage of justice.

(2) If this section applies, the person has the right to be compensated according to law.

The obvious questions that arise when considering the codification of such compensation include the following:

- Should people wrongfully convicted and jailed automatically receive compensation?

- If so, should the amount be calculated on time spent behind bars? (In the US a number of states have a set amount of compensation for each year of imprisonment – it varies.)

- Should the severity of the crime effect the compensation? (eg the more serious, the more the compensation)

- Should the emotional toll be calibrated and costed?

- Should the cause of the wrongful conviction also be a contributing factor (eg prosecutorial or judicial error or malfeasance)?

- Should compensation guidelines be uniform across all Australian state and federal jurisdictions?*

- Should (excessive) delay between arrest and conviction be considered? (eg Robert Xie spent a total of 9 years in jail before his conviction.)

- Should compensation payments be monitored / regulated by an independent judicial body?

- Does the state have a moral obligation (see below) to compensate the wrongfully convicted? (Such responsibilities are evident elsewhere: when a Government bus/train that damages your car / when Government employee defrauds a citizen / when government acquires land or property by compulsory acquisition / when a state agency breaks the law that impacts on citizen/s)

Moral obligation:

On 3 August 2015 Paul Bibby of the Sydney Morning Herald reported “Wrongful detentions: NSW Police to pay $1.85 million in compensation after settling class action” – The NSW Police force has agreed to pay a total of $1.85 million to scores of young people across the state who have been wrongfully arrested, imprisoned and in some cases strip searched due to errors in the police database.

More than four years after a class action was launched in the NSW Supreme Court on behalf of the youths, lawyers for the police agreed to an in-principle settlement on Friday under which each person receives compensation according to the harm they have suffered.

“It’s been absolutely crystal clear that there was a major problem in the COPS database and that young people were being very, very badly affected by it,” said Edward Santow, the CEO of the Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) which helped run the case. ‘There was a moral and legal obligation to solve the problem,’ said Edward Santow. “There was both a moral and a legal obligation to resolve the problem and to assist those young people who were badly affected.” As many as 100 people were victims of basic errors in the Computer Operational Policing System (COPS) in relation to bail status and conditions.

The errors occurred when bail conditions were either dropped because a case was finalised, or varied to allow for work, study or family commitments, but this change was not added to the database. As a result the young people involved were wrongly arrested for breaching bail.

*

On 9 December 2016 Emily Piesse of ABC reported “Couple tasered, detained by police in Fremantle awarded more than $1m in damages”. A couple who were tasered by police in Fremantle eight years ago have been awarded more than $1 million in damages after suing the state for false imprisonment and assault. Catherine Atoms and Robert Cunningham were walking past the Esplanade Hotel at night in November 2008 when they stopped to help a man lying in bushes nearby. Police arrived shortly afterwards and tasered the couple, before handcuffing them and charging them with obstructing a public officer. The charges were later dismissed, however the couple took civil action against the State Government and three police officers. Today, District Court Judge Felicity Davis found in favour of the plaintiffs, ruling the couple was subjected to battery, false imprisonment and misfeasance in public office. Atoms was awarded $1,024,822.11. Dr Cunningham, an associate professor at Curtin University’s Law School, received $110,304.10.

Some of the challenges:

* Getting the states to agree on uniform guidelines would be a challenge…see their (dis)unity in the Covid experience; unequal guidelines would be morally and ethically wrong (as is the status quo) and contrary to Australian human rights requirements

– Resistance from politicians and others who refuse to accept some legal exonerations (eg in SA, the ex-gratia payment to Henry Keogh – see above – after his successful appeal, was attacked by some Labour politicians who still regarded Keogh as guilty, as did some after Gordon Wood was acquitted, and many also did after Cardinal Pell was acquitted by the High Court.)

– Drawing up a universally applicable and acceptable set of fair & reasonable guidelines.

***

Our reader Maris Valentine, wrote in a Comment on 26/7/21: “Perhaps there should be mandatory damages payout figures depending on the seriousness of the alleged crime/s and the length of prison time served; also the amount of publicity the conviction generated. After all, there are mandatory sentences for certain types of crimes, and where there are not mandatory sentences, there are ‘community expectations’ that judges tend to adhere to.”

Andrew Wilkie MP Independent Member for Clark, Tasmania, told this writer: “I strongly support the proposition that people unjustly imprisoned be fully compensated. And if Sue Neill-Fraser’s conviction is overturned, she should receive a very substantial sum for loss of her reputation, income and freedom.”

The money

Compensation payments are decided by governments but underwritten by taxpayers. It is obviously in the interest of justice and a ‘fair go’ that deserving recipients be properly compensated for mistreatment by the law. And as compensation is an added cost of the process also paid by the taxpayer (legal costs of prosecution) minimising wrongful convictions should have a high priority for all of us, along with our concern for justice.

For the most extreme example, consider the May 2014 Eastman inquiry that resulted in David Eastman’s 1995 conviction for the 1989 murder of Asst. Police Commissioner Colin Winchester being overturned, which cost the ACT $10 million and legal aid for Eastman is estimated at a further $3 million. That’s just for the inquiry after the trial! “However, it hardly stretches credulity to suggest that pursuing, prosecuting, imprisoning and defending Mr Eastman (via legal aid) over three decades cost twice or three times the expenses of the latest inquiry and retrial — taking the amount beyond $60 million or even $100 million,” according to abc.net.au. Eastman was paid compensation of $7 million after spending almost 20 years in jail. (Compares to Keogh’s $2.75m for roughly the same time in jail … higgledy-piggledy in extremis!)

Paying millions in running a flawed criminal case and perhaps millions more in compensation makes it a compelling argument to introduce the reforms that have been well articulated for some years, in order to minimise wrongful convictions.

The reforms

Here are reforms we have promoted since 2014, which were formulated at the Symposium on Miscarriages of Justice, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Nov. 7 & 8, 2014, organised by Bibi Sangha and Dr Bob Moles:

Police investigations:

* training to avoid ‘tunnel vision’ approach

* training to adhere strictly to investigation procedures, notably

* accurate record keeping, witness statements, evidence collection

* management culture to emphasise serving the court not the prosecution

Forensic scientists, laboratories, professional bodies:

* develop a system of quality standards, with documented policies and procedures

* training to explain evidence in court so that it is understood

* requirements for validation of evidence

* training to avoid contextual bias

* emphasis on serving the court not the police / prosecution

Prosecution:

* adherence to rules of law (e.g. not presenting speculation as fact)

* to explain forensic evidence rationally

* presentation of evidence fairly

* seeking conviction must be subservient to seeking of truth

* accountability: penalties to apply for misconduct

Judges:

* to demand clarity and understanding by jury of scientific & forensic evidence

* to ensure prosecutors adhere to rules of trial behaviour and fairness

* accountability: penalties to apply for misconduct (as defined, acting contrary to rules)

The causes:

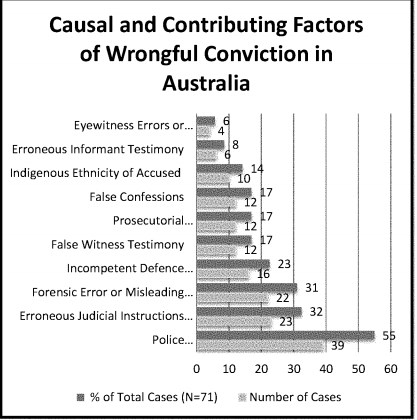

Research by Dr Rachel Dioso-Villa, Senior Lecturer in Criminology Law and Society at Griffith University, into causes of 71 wrongful convictions (1922 to 2015) shows why such reforms are needed – see the chart below, which reveals that 1 – police error *, 2 – judicial error * and 3 – forensic error * were the three most frequent contributing factors. (In both the Sue Neill-Fraser (Tasmania, 2010) and Robert Xie (NSW, 2017) cases, all three contributors were observed.)

* see Talking to Strangers for more on police and judicial error

Could you please review this wrongful imprisonment case

Hello, I am DUONG. I have been waiting for almost 05 years in Custody in Queensland- Australia without Trial and no evidence just for only one charge Cannabis trafficking. This case was absolutely wrongful imprisonment. I can not see any reason why I should not sue them. This is a gross miscarriage of Justice and unacceptable. I am determined to pursue this lawsuit case till I win. I wanted to clear my name and make them accountable for what they have done to me and my family. I attached some documents for your review. I got all the information and evidence here. If you can please help me then I will send all the documents to you immediately. Please review this case and help me. I look forward to hearing from you. Thank you.

Kind regards

DUONG QUOC DUNG

Thanks for your comment and I’m sorry to hear of your predicament. I wish I could help, but you need a lawyer for that. I’m a journalist.

Where in Queensland are you being held in custody?

Hi

I’m working on a Ph.D proposal that aims to explore the development and implementation of a right of compensation for people who have been imprisoned on remand but who are later not found to be guilty of the matters they were charged with. There are at least a dozen countries in Europe where there is a right of compensation for pre-trial detention for those who are not convicted, and in Germany, such a scheme has been in operation since 1971. Not only can the remanded person claim compensation but so can his dependents. I want to explore the possibility of introducing such a scheme in Australia. I would be delighted to hear personal stories from people who have been imprisoned on remand and then released without conviction.

I was imprisoned for 7 months and granted an appeal, which I successfully had all charges acquitted. I spent 2 1/2 years on bail conditions which nullified me travelling for sorry buisness for my tribal mob and missed the oppurtunity to walk my daughter down the aisle for her wedding due to the allegations against me and the rift ,rumours and speculation by immediate family members. I have 2 grandsons, whom I’ve only had the oppurtunity once to hold when I made a very brief 4 day trip to see him. The other is nearing 4 year old and I have never physically had the oppurtunity to bond with. The mental,emotional and physical trauma is on going and I would like to know what steps I can take to help restore my dignity and financial situation which has left living in a friend’s garage since I walked away from a toxic relationship, sacrificing any contact with my now 5 year old son.

Thank you and look forward to some sort of response.

Sorry to hear your sad story, Russell, and while I can offer sympathy, I can’t offer a meaningful and useful response as to how you might be compensated. Of course, you should be compensated, even though money doesn’t fix some of your emotional pain. Perhaps one of our readers knows what you might try…best wishes.

Interesting read.

I’d like your opinion on home detention.

Myself, I’m on home D for a month now. Certainly better than being in jail, but worse and restraining than normal life. Also comes with significant financial lose. In my opinion I should be entitled to compensation when find not guilty.

I certainly agree that persons found not guilty of a crime should be compensated. My rationale is that the legal system must be held more accountable than it is. It is a responsibility of the state to protect its citizens – that applies to protection from its own agencies.

Very interesting reading.

Something not mentioned is prisoners being detained and held in maximum security VIC prison’s beyond expiry of sentence.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions Emergency Management Days were granted in VIC if eligible. An automatic process by Corrections Victoria for those deemed eligible up until having those EMD actually being applied to the sentence.

*** clarification purposes Corrections VIC says “yes Mr Smith your eligible for 100 cans of softdrink we will have someone deliver them to you”…clearly a prisoner can’t collect the softdrink so a ‘courier’ clearly the other VIC Corrections department must deliver in case of softdrink or apply in the case of days being removed from sentence.

Currently I am a fully discharged Federal Prisoner and was a fully discharged Federal Prisoner prior to the first whisper of Crimes Amendment Remission of Sentences Bill 2021. I have served every single day of any sentence imposed. I was sitting in a cell at Port Phillip Prison eagerly awaiting softdrink that Corrections VIC promised. That CV courier never showed and eventually the time came when the big guy in Canberra gave instructions to CV who instructed a “key turner’ to do the obvious.

I need an eagle who likes to hunt and can help me get my promised drinks. Please email your law firm contact and I will call.

mikeysemail@protonmail.com

I ask. How do we, in a modern democratic society bring about change?

Through the democratic political system.

And if it is corrupt? What then?

And the Left are as corrupt as the Right.

Keogh at the top of the list. In my opinion Keogh either murdered Anna-Jane himself or hired someone, take your choice. Either way Keogh is guilty.

I am still waiting for Urban to ask for my version of events.

Moles got Keogh out of gaol based upon a discredited autopsy report. A faulty report does not make Keogh innocent. There is a chance that Madock may have been right.

Moles goofed.b

The above table is misleading.

There is a continuing perception on this site that innocent people are in gaol because of error. Wrong.

The police build a case around a nominated suspect before the evidence is in.

Real evidence which does not suit is dropped and invariably the case is built on circumstantial evidence. The case gets manipulated every way possible.

Andrew, you have been singing the song of Keogh’s innocence for sometime . How about reconsidering your position. It could be said that you have used similar methods to the police, only in reverse. You deem Keogh innocent and build the case around that view.

Keogh spent the first night in their home ‘cleaning up’. What! it was a potential crime scene.

I suggest the authorities paid Keogh out for reasons of expediency. To reopen the case could generate unwelcome publicity. Better to payout and move on.

1 – I invited you to email me details of your evidence against Keogh some time ago (purely out of curiosity). So please send it and stop pestering me about it.

2 – I do not find your claims about a ‘discredited autopsy report’ to have merit, given the credibility of the expert witnesses who tore it apart at appeal, not to mention Manock’s appalling track record of malpractice, incompetence and lies.

3 – ‘There is a continuing perception on this site that innocent people are in gaol because of error.’ you say. You are quite wrong; we have identified the many failures by police, prosecutors and even judges to abide by the rules that have resulted in wrongful convictions. BTW, ‘error’ can also mean fault…

4 – ‘The police build a case …etc’ you say. Exactly. It’s called tunnel vision and we call it out at every opportunity.

5 – The SA Government’s ex gratia payment to Keogh was indeed partly driven by expediency, in my opinion, because the embarrassing cancer of Manock would have to be paraded in public in some detail in any further enquiry into the case…even after Keogh spent 20 years in jail.

very comprehensive again Andrew. I am drawn to one point in particular, where the costs associated with the wrongful conviction of Eastman.(just the cost of the inquiry following the trial running into the milions) What has been the cost to the Tasmanian taxpayer to bolster the maintenance of the miscarriage of justice of Sue Neill-Fraser. A huge cost to avoid admitting error.

It would be too embarrassing for the Government to reveal – but Tasmanians should nevertheless demand to know; it’s their money.

agree and it should be a top priority; if we had an equivalent of Senate estimates at a state level or revealed publicly in the ODPP Tas budget!

Tas budget estimates committee hearings commence shortly

https://www.parliament.tas.gov.au/Parliament/Combined%20Sitting%20Schedule%202021.pdf