Andrew L. Urban.

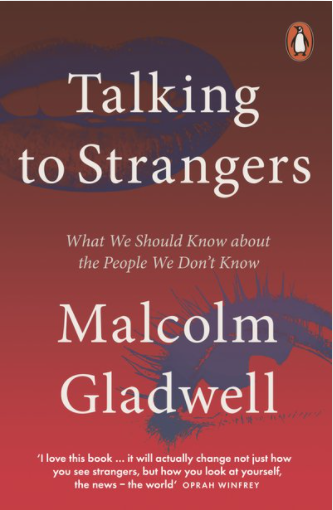

The full title of Malcolm Gladwell’s book is Talking to Strangers: what we should know about the people we don’t know. For someone who did in fact talk to many, many strangers on the streets of Australia with a TV camera for my prime time SBS program, Front Up in the 90s, the subject matter is irresistible. And the book proved to be unputdownable … plus highly relevant to the subject of wrongful convictions.

Malcolm Gladwell is quoted as saying “I’ve never been a writer who’s looked to persuade his readers; I’m more interested in capturing their interest and curiosity.”

Malcolm Gladwell

He succeeds at that. Reading this book from my unique perspective (as an interviewer of strangers and an investigative journalist in the field of wrongful convictions) my interest is aroused on every page, with every example, with each observation. I can relate to the notion of trying to ‘assess’ strangers on the flimsiest grounds.

In my case, assessing strangers was limited to guesswork as to how they would react to me fronting up to them out of the blue in the street with a microphone and TV camera, asking questions about their lives. Rejection was the expectation…how much rejection could I take in a single day?

Gladwell’s book uses real life examples from the ‘real life’ files (eg Sandra Bland, Amanda Knox), where the stakes are so much higher than personal rejection of a journalist/interviewer. But the currency of inter-stranger communication is much the same; just for different ends.

What strikes me is how accurate Gladwell’s observations are (in the context of my own experience) about the traps we fall into when trying to assess strangers. By ‘assess’ I mean understand, deconstruct, uncover … even analyse.

As one of his readers puts it, “It’s very difficult to tell when people are lying. According to Timothy Levine, the academic psychologist on whom Gladwell relies for his basic argument, the presumption that people tell the truth is almost universal…” And that’s where our reading journey starts.

In the tragic case of Sandra Bland, a police officer completely misread the behaviour of the driver and the situation escalated from 0 to 100. He had been behind her on the road in a peaceful village, not a crime hot spot. She changed lanes to let him pass… he stopped her for failing to signal. Then when she lit a cigarette, the officer told her to put it out. He ended up dragging her out of her car and charging her, down at the police station. Three days later she committed suicide in the cell. No, not because of the traffic stop; that was just the last straw, on the first day of a new hopeful chapter in a depressed life. Gladwell details this story with transcripts of the interaction and also of the investigation into the officer. Both are illuminating – and sad.

In the amazing Amanda Knox case, the police make similar mistakes in grand order. Knox was convicted but later acquitted of the murder of Meredith Kercher, a fellow exchange student who shared her apartment in Perugia, Italy.

As for judges, you’d think they’d be better than average at recognising who is telling the truth. Gladwell refers to a study in which judges scored just 54% – a tad over what a flip of the coin might give you.

In another study, Harvard economist Sendhil Mullaianathan, along with three elite computer scientists and a bail expert, built an artificial intelligence system and put 554,689 cases through it with the command to make a list of 400,000 who could be released on bail (with the same information that the courts had). “The people on the computer’s list were 25% less likely to commit a crime while awaiting trial than the 400,000 people released by the judges of New York City. “In the bake off, machine destroyed man,” writes Gladwell.

Gladwell also feeds our interest and curiosity with relevant ‘stranger’ stories about meetings between Hitler & Chamberlain, and Cortes & Montezuma.

EXCERPT

A trained interrogator ought to be adept at getting beneath the confusing signals of demeanor, at understanding that when Nervous Nelly overexplains and gets defensive, that’s who she is—someone who overexplains and gets defensive. The police officer ought to be the person who sees the quirky, inappropriate girl in a culture far different from her own say “Ta-dah” and realize that she’s just a quirky girl in a culture far different from her own.

But that’s not what we get. Instead, the people charged with making determinations of innocence and guilt seem to be as bad as or even worse than the rest of us when it comes to the hardest cases. Is this part of the reason for wrongful convictions? Is the legal system constitutionally incapable of delivering justice to the mismatched? When a judge makes a bail decision and badly underperforms a computer, is this why?

Are we sending perfectly harmless people to prison while they await trial simply because they don’t look right? We all accept the flaws and inaccuracies of institutional judgment when we believe that those mistakes are random. But Tim Levine’s research suggests that they aren’t random—that we have built a world that systematically discriminates against a class of people who, through no fault of their own, violate our ridiculous ideas about transparency.

The Amanda Knox story deserves to be retold not because it was a once-in-a-lifetime crime saga—a beautiful woman, a picturesque Italian hilltop town, a gruesome murder. It deserves retelling because it happens all the time. “Her eyes didn’t seem to show any sadness, and I remember wondering if she could have been involved,” one of Meredith Kercher’s friends said.

Amanda Knox heard years of this—perfect strangers pretending to know who she was based on the expression on her face. “There is no trace of me in the room where Meredith was murdered,” Knox says, at the end of the Amanda Knox documentary. “But you’re trying to find the answer in my eyes …. You’re looking at me. Why? These are my eyes. They’re not objective evidence.”

QUOTE

The first set of mistakes we make with strangers—the default to truth and the illusion of transparency—has to do with our inability to make sense of the stranger as an individual. But on top of those errors we add another, which pushes our problem with strangers into crisis. We do not understand the importance of the context in which the stranger is operating.

QUOTE

“You believe someone not because you have no doubts about them. Belief is not the absence of doubt. You believe someone because you don’t have enough doubts about them.”

QUOTE

“To assume the best about another is the trait that has created modern society. Those occasions when our trusting nature gets violated are tragic. But the alternative – to abandon trust as a defense against predation and deception – is worse.”

#Talking to Strangers: what we should know about the people we don’t know

#Talking to Strangers: what we should know about the people we don’t know

Published September 10th 2019 by Little, Brown and Company

Enjoyable reading here.

About 15 years ago, I was at a party at a restaurant at Customs House, Circular Quay, where, at one point, I fell into conversation with another who told me he was a judge.Having never before conversed with a judge in any mileau or social setting, I recall asking ,delectably, what felt the most natural of questions, “ Did he get judgements wrong. He replied, matter of factly, “yes”. Naively, -I now know- , I was stunned.

There was an interesting moment at a Mention between the 3rd and 4th trials of Robert Xie. The new Judge – Elizabeth Fullerton – actually said aloud words like: “Well, who am I to trust – the Prosecutor or the Defence – obviously only one of you can be telling the truth.” I’d sat through most of the previous two trials. The Judge had not seen any of the previous two trials. To my horror, rather than check the records to find out, she jumped to the wrong conclusion. This had a catastrophic effect on subsequent events.

I have seen judges who actually use logic and data to try to determine justice and the truth – Justice Peter McClellan and Julie’s Judge for example – instead of being overconfident of their ability to determine truth from demeanour, eyes and expressions.

Almost ten years ago, Tom Bathurst was fairly new to his job as Chief Justice of NSW. When asked by Ray Hadley in an interview (no longer on the internet, alas) whether judges are affected by the media, Justice Bathurst replied with words like: “Of course we are – Judges are human, so – like everyone else, the media affects us. My role is to try to make sure that such effects are minimised by the Judges who work for me and that they don’t let the media affect their decisions.” A great answer to a good question.

Justice Bathurst is clearly a man who answers questions truthfully (as above) – a man of integrity, intelligence and ability. So why has Justice Bathurst been on at least two appeals which clearly have been miscarriages of justice? I think there are two reasons. Firstly, as Julie points out, Judges get some judgements wrong. Secondly, Justice Bathurst’s background until he became Chief Justice was not in criminal law, so Justice Bathurst lacked the experience which helped Justice McClellan ignore suspicion, innuendo and politics to make wise decisions in many difficult cases.

(A “Mention” is when the Judges calls in the lawyers for each side, before a trial, to sort out bits and pieces relating to the upcoming trial.)

Astute observations, Peter.

Ever since the English usurped the meme of JUSTICE and created The English Adversarial Justice System and its LEGAL COHORT of Lawyers and Judges, and The Separation of Powers between Government and The Judiciary, WE THE PUBLIC have been inexorably brainwashed to accept that all persons sycophant to it and stipended by PUBLIC TAXATION, are ALL KNOWING, intelligent and well meaning in intent of purpose.

Fact is, the reverse is true.

WE THE PUBLIC are ALL their potential VICTIMS, kept ignorant of their real purpose by their use of a foreign language called Legalese within their inner sanctum and their Courts so that Juries are destined to suffer confabulation of the mind. Which would not be so likely if the judgement jurisdiction was in an always open to the public forum and the language used was everyday common English accompanied with the application of common sense to the Case at hand at all times. It is US versus THEM. The Justice System being PUBLIC ENEMY NUMBER 1.

Your views on the justice system will find a friendly echo in the work of the late Evan Whitton, who considered the legal system to be a cabal. We published some nuggets from the book Our Corrupt Legal System you (and other readers) may find darkly amusing … and relevant.

Thanks Andrew.

I notice you pick up on a quoted figure in the book : “As for judges, you’d think they’d be better than average at recognising who is telling the truth. Gladwell refers to a study in which judges scored just 54% – a tad over what a flip of the coin might give you.”

Clearly judges should not be evaluating on the basis of who they “judge” to be telling the truth, but on the facts. They are supposed to go on the facts. If there are no facts, then there are no facts and Crown Prosectors should not be prosecuting bankrupt cases.

And I have mentioned before, a study that quoted judges and police on average only getting truthfulness right based on demeanour at about 45% – so a tad less than a flip of the coin.

Whichever figure is right, 45% or 54%, judges need to go back to school and find out that they do not have some God-given or superior judgement. They have to stick with their legal training and total up the facts.

I am beginning to think that although individual judges should be indemnified when they are doing their job in good faith, [but not if it can be shown that they exceeded the limits of their jurisdiction] nevertheless, the various Departments of Justice definitely should be liable for the crime of “getting it wrong” because of the enormous damage it does to the wrongly convicted and the wrongly convicted’s family and friends.

Perhaps there should be mandatory damages payout figures depending on the seriousness of the alleged crime/s and the length of prison time served; also the amount of publicity the conviction generated. After all, there are mandatory sentences for certain types of crimes, and where there are not mandatory sentences, there are “community expectations” that judges tend to adhere to.

You raise the valid issue of compensation for wrongful convictions – a really wicked problem … so many moving parts. Different jurisdictions, variable circumstances, variable causes … etc etc. It’s a dog’s breakfast, as they say, and we’ll be looking at it.

excellent topic with some excellent, insightful comments but specifically in addition to your point Maris about % of correct judgements by judges; an example of the arbitary nature of this was dominant in the trial of Sue Neill-Fraser. An example stands out when Justice Blow admits re some preposterous evidence put forward by a prosecution witnesses story, the judge accepts the person has a record of crimes of dishonesty but in this case accepts he is ‘telling the truth”. How significant an error of judgement? Unknown maybe, but in reality may have swayed a jury to a miscarriage of justice so far of 12 years!

Dear Andrew.

Thank you for your works and we are all dismayed by the inability of the Tasmanian legal protection to act with any morality. They will and have demonstrated a callus ability to kick the can down the road.

I have and continue to follow this case and have several times thought that, does the Queen still have executive powers over the Australia?

So Andrew, I have been reading “The Executive Institution of Mercy in Australia. The case for moral reform. 312 onwards.

Now I am not versed in law and dyslexic so it is very complicated but does seem to have some sense in areas that we could use go take a different line of attack.

Stay strong Sue and be safe everybody.

Stephen

Wow , Andrew, I am glad we are working together. I watched parts of a couple of interviews, your mind is very active and you have no social anxiety, or you deal with it well.

I would like to explain a court situation.

I appealed a magistrates conviction after the event, [incarceration] which would damn near be impossible in any event.

I represented my self against the police prosecutor in front of a Supreme Crt Judge in Tasmania. The Judge was known to be a fair and Just Judge.

This was for a conviction of breaking a restraining order by playing a guitar in a public place.[busking, same place same time Mon-Fri for weeks}[until their sordid minds came up with a plan which was obvious to me but I did not back down and fell into their trap and paid the price for freedom. They locked me up.]

In court, bearing in mind it was my 2nd attempt at representing myself with my social anxiety [and inferiority complex]; the police prosecutor had a stack of books 1/2 a metre high and wanted to start quoting from previous court decisions.

I called out, “this is a farce”, and the Judge said, This is a Farce? and I said yes.

The Judge said appeal dismissed, or what ever.

Because I did not have the communication ability to explain anything. I just shut down.

End of story

Royal Commission Tasmania Police.

Federal Royal Commission Tasmania.

Establish a Federal Criminal Case Review Commission.

Establish Federal Whistleblower Protection.

Release Sue Neil-Fraser…….NOW.

One of the reasons my generation is so poor at reading demeanour or detecting lies is the boom in the last 45 years of misleading popular books and training about body language. Some of the misinformation in media such as the best selling book Manwatching by Desmond Morris and in some of Allan Pease’s books has been shown by science to be wrong, but the errors have taken hold in the general public, leading to errors in areas such as job interviews and criminal cases.

To give one example. On Day 1 of the first trial of Robert Xie, the Judge Peter Johnson told the jury not to write notes because that would distract them from their important task of watching the faces of the witnesses, which he said was a vital part of their role. The Judge seemed to have no idea that jury members lack skill at reading demeanour. The series of trials went downhill from there.

Excellent point Peter.

I have to say. In my first appearance of guilty of playing guitar in a public place; I was locked up in Risdon Maximum; I was represented by legal aid; a brand new lawyer from uni.

I was in the dock, the lawyer was at his table. I beckoned him from his table to the dock to talk, twice; and the magistrate told him to stop going to talk to me in the dock.

Yeah man. This is Tasmania Justice.

Bring it on.

Hey , this was war; as a taxi driver before it crumbled I signaled a cruise ship as it departed down the river predawn ; SOS morse code repetitively. And I wrote a letter to the Captain of US Navy ship tied up at the dock. I did not deliver the letter until the gates were closed on the dock and I asked the US Navy Personal to deliver my letter to the Captain of the ship.

You seem to have had a difficult past Owen, but maintain your faith in humanity, it, faith, is not a structured, echolon based, stratified, hypocritical abstract concept, generally just a concept of accepted values, lived, practiced and proven over time.

From each according to their capabilities, to each according to their needs. Treat others as you would like to be treated yourself and respect the values of others, while being overtly willing to protect the fore mentioned when the necessity prevails. “They don’t like it up em”, as Corporal Jones frequently stated.

Thanks for the kind words Robert, Corporal Jones was certainly a mentor for the younger, as was Captain Mainwaring.

We will never lose if we have a team as dedicated as them.

Wow!!! I find that instruction/direction astonishing.