Andrew L. Urban

How really reliable is testimony from expert witnesses? How can juries and judges tell if what they are told is unbiased, grounded in solid scientific knowledge and not just opinion? How should such witnesses conduct themselves? Try this check list.

“My objectivity and integrity are central to my testimony. I will only act as an expert witness under the following conditions:

- My testimony addresses matters on which I am familiar with the scientific evidence.

- I will be fully informed by the lawyers about relevant matters in the case.

- The case deals with an important issue that will affect others in a positive way. In short, there must be some wider benefit.

- To help ensure that my testimony is free of bias, I only work on an hourly basis, with no contingency fee.

- To help ensure that my testimony will not be thought to be biased, I must be fully paid (including expected time for testimony) prior to testifying before a Court or Arbitration Board.

- I will abide by the Guidelines for Science. (The sixth condition was added in 2019.)”

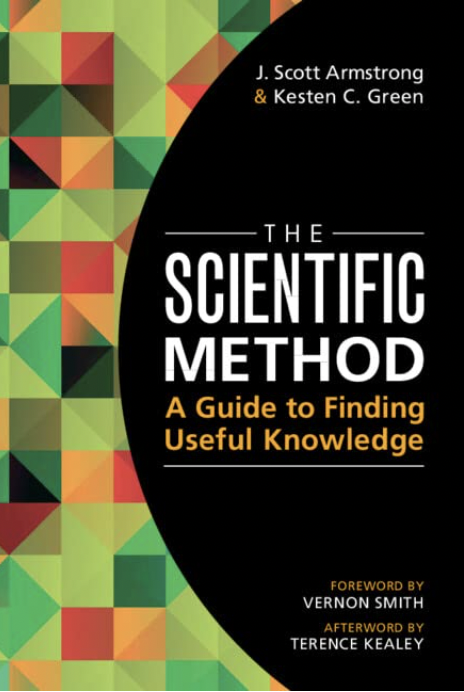

This check list, with similar intent to doctors’ Hippocratic oath, was drawn up by the authors of a valuable new book, THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD: A Guide to Finding Useful Knowledge (Cambridge University Press). The authors themselves, J Scott Armstrong & Kesten Green, offer an oath of their own:

Authors’ Oath for The Scientific Method:

Kesten C Green

(1) We, one or both of us, have read each publication that we cite for a substantive finding.

(2) We attempted to contact the authors we cited for substantive findings to help ensure that we accurately described their findings, and to determine if we omitted relevant scientific papers, especially those with scientific evidence that conflicted with our findings.

J Scott Armstrong

(3) We used the Criteria for Compliance with the Scientific Method from our book, and believe the book is compliant with the scientific method.

(4) Voluntary disclosure: We received no external funding for writing this book and have no conflicts of interest.

There is much made of the notion of science in nearly every aspect of our political decision making and public discourse, not least in the high value, socially divisive issues around managing Covid 19, climate change policies and gender identity. But the scientific method is not so often discussed – hence not well understood by the general public, the media or the politicians. We should all get familiar with the principles, at least ….

proper science, used properly

Frits Van Beelen

In October 1971 Frits George Van Beelen, a 25 year old carpenter with boy-next-door good looks, was charged with the July 1971 murder of 15 year old schoolgirl Deborah Leach, on Taparoo Beach in Adelaide. Following a 71 day trial in the Supreme Court of South Australia, on October 19, 1972 the jury returned a verdict of guilty – and he was sentenced to death.

There were no witnesses and the only evidence was circumstantial – and scientific, if that word isn’t too presumptuous in the circumstances. Indeed, the volume and complexity of the scientific evidence was large. After a successful appeal, a second trial was held. At the second trial, Professor Bevan was called as a witness for the defence. His evidence related to the identification of paint samples. Under cross examination Prof Bevan made the following point: “I see no reason why if the legal processes are going to use science it should not use proper science.” To that basic proposition the second proposition can been added, “and use science properly”.

In their easily accessible book, the authors clearly revere the scientific process and present powerful propositions as to how emerging scientists (and established ones) should approach their subject. It is almost like a catechism for science. The Van Beelen case is just one (dramatic) example of the failure to use science properly – with extraordinary consequences.

The second trial in 1972 also ended in a guilty verdict. “At that time the Privy Council was still the final Court of Appeal. We journeyed to London and presented his case to the Council. Our Appeal was refused,” recalls Kevin Borick QC.

“Forty years later,” Borick continues, “when the new s353A legislation was passed to allow a further appeal, we sought an opinion from professor John Horowitz as to the evidence relating to the time of death.

“On October, 2, 2017 the High Court granted special leave to Van Beelen based on the Horowitz evidence. This evidence showed that “The precision of Dr Manock’s one hour interval was a critical component of the Crown case that the death had occurred no later than 4.30 pm. Professor Horowitz’s evidence has shown that Dr Manock’s one hour time period had no scientific support and was wrong.”

“On November 8, 2017 the High Court found (among other things) that: Dr Manock’s opinion was based upon acceptance that there is a normal rate of gastric emptying in the human population. Kourakis CJ was right to say that Professor Horowitz’ evidence based on the results of objectively validated studies falsifies the basis for that opinion. Had the results of these studies been known at the date of the trial, Dr Manock’s opinion as to the time of Deborah’s death should not have been admitted over objection.

“Yet still the appeal was dismissed, the judges refusing to allow us (the defence) to argue that Dr Manock lacked professional ‘good faith’ and thus his testimony concerning clothing fibres from Van Beelen mixed with the victim’s clothing should also be disregarded.” This is a succession of miscarriages of justice in which all the legal participants, including judges (but excluding the defence), failed to demand adherence to the scientific method and were thus party to a terrible injustice.

Apart from the illogicality of the Court’s decision to dismiss the appeal, this case is part of Australia’s greatest – and still unresolved – forensic science scandal. Dr Colin Manock, the chief forensic pathologist of a modern Australian state who was not qualified to do his job, was discredited by the legal establishment, yet he continued over decades to perform thousands of autopsies and the like, including 400 serious criminal cases….

The long retired Dr Colin Manock looks old these days, his eyes half hidden behind his spectacles. If you passed him in the street, you wouldn’t guess he once performed an autopsy in the open air. In public. It was in the main street of Mintabie, 980 kms northwest of Adelaide, the remote opal mining community (now closed). It was 1978 and an Aboriginal man had been found dead, in mysterious circumstances. The Coroner sent a team to investigate. Refusing an offer of a cool room for the procedure, the State’s forensic pathologist set up a make shift morgue in the street and proceeded to perform his gut wrenching task. After Dr Manock had removed the bodily organs from the chest, he is said to have used a ladle to scoop up some of the body fluids and to have made an ‘inappropriate remark’ – said to have been, ‘does anybody fancy a slurp?’

The report is part of a sworn affidavit by a former police officer who witnessed the event.

The observation made by a Justice of the High Court about Manock’s evidence in another case, that of Emily Perry (1982) is damning. “… an appalling departure from acceptable standards of forensic science in the investigation of this case . . .”

This is the Dr Colin Manock who not only lacked professional ethics; he lacked the qualifications to do his job. This is the Dr Colin Manock who, it was once said, described Kevin Borick QC as his bête noire …

This example, as extreme as it is, should have alerted the criminal justice systems around Australia to the dangers of unreliable expert testimony; testimony that has jumped the guardrails of the scientific method.

It is of course not the only case of science being subverted in court.

The best first thing that could happen in the criminal justice system is the rending apart of the police from the forensic services around the country, and the establishment of a full scale national forensic institute. The courts would benefit from more reliable forensic evidence. The first thing to note is that flawed forensic evidence often features as a contributing factor in wrongful convictions: 22% according to Australian research (Griffith University). Another major contributing factor is police work, at 39%. Forensic services work very closely with the police – too closely, it is suggested.

Two critical American reports, published in 2009 and 2016, led to major changes to the US and British legal systems. Not so in Australia. (It’s one example of how the self-governing justice system is resistant to reform.)

The 2009 report, by the US National Research Council (NRC), advocated for a large, National Independent Forensic Institution (NIFS), to improve the delivery of forensic sciences evidence in criminal trials. Australia already has a body similar in name*, but it can’t do the job envisioned for such a body by the NRC. It is small, with half dozen (very personable looking) staff and it is “neither independent nor transparent”, according to Professor Gary Edmond, Australian Research Council Future Fellow, and Director, Expertise, Evidence & Law Program, School of Law at UNSW.

(* The National Institute of Forensic Science is a directorate in the bosom of the Australia New Zealand Policing Advisory Agency.)

Forensic services should be independent of the police. As the NRC report put it, it is “vital that any entity that is established to govern the forensic science community cannot be principally beholden to law enforcement, rather it must be equally available to law enforcement officers, prosecutors, and defendants in the criminal justice system.”

“In advocating a national institute the NRC Committee was conscious of the historical proximity of forensic science and medicine to law enforcement. It insists on distance and autonomy because the ‘best science is conducted in a scientific setting as opposed to a law enforcement setting,’” writes Edmond, in his paper What Lawyers Should Know About The Forensic Sciences (Adelaide Law Review). “The title of this essay uses the term ‘forensic sciences’ rather than the singular ‘science’. The distinction is significant. It is important to recognise variation across the forensic sciences.”

Authors Armstrong and Green would no doubt agree.

THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD: A Guide to Finding Useful Knowledge

THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD: A Guide to Finding Useful Knowledge

J Scott Armstrong & Kesten Green

Cambridge University Press, June 30, 2022

J Scott Armstrong is an author, forecasting and marketing expert, and a professor of Marketing at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

Kesten Green is a leading researcher on forecasting methods and applications. He has developed new and better forecasting methods for business and public policy, and his research is widely cited. He has proposed and tested a unifying theory of forecasting, the Golden Rule of Forecasting, and is responsible for a review of evidence confirming the superiority of sophisticatedly simple forecasting methods over complex ones.

See our Section Forensic Evidence for more on this topic

See our Section Shaken Baby Syndrome for more on this topic

Why is there so much damming hearsay evidence against Susan Neill-Fraser, is it true or false? Who is LYING?

You’d have to be more specific if you were hoping for an answer …

Fighting injustice and in particular miscarriages of justice is a David and Goliath inequality sized battle within the present business model (system) as outlined precisely by previous comments. It requires a different approach. Australia is lagging as usual yet models of reform beginning with UK with its Criminal Cases Review Commission of many years now and taken up by more progressive countries for example Canada are within reach. Australia has historically based its model of law on the British so just needs a push over the line to get a CCRC up and running where a case may be reviewed without the usual limitations in an appeal.

positive action!

An old friend of Sue and Bob has started a petition specifically for a CCRC to be established in Australia, which readers may want to support:

https://www.change.org/p/justice-for-sue-neill-fraser-is-justice-for-all

Thank you Rosemary. Signed the petition and forwarded it to friends. A CCRC long overdue, especially over there. Once thought it was a great destination to travel too. Not so now. Guess I have learned how the treatment of one it’s citizens, is not worth the risk. It would appear that Andrew Wilkie, MP is the only credible politician over there. Even his voice gets lost in the wilderness of a what I believed was the most wonderful State in Australia. Sad.

The one great principle of the English law is to make business for itself. Viewed by this light it becomes a coherent scheme and not the monstrous maze the laity are apt to think it. Let them but once clearly perceive that its grand principle is to make business for itself at their expence, and surely they will cease to grumble. – Charles Dickens.

The late Evan Whitton understood the law racket better than most. His book “Our Corrupt Legal System” is well worth reading.

It is indeed worth reading. Meantime, here is our story on this work:

https://wrongfulconvictionsreport.org/2018/01/13/bare-faced-lawyers-confessions-of-the-legal-profession/

Andrew, I am more depressed than ever. I should never have skimmed. But I will stay on board in my tears.

God Bless Sue Neill-Fraser and other victims of Tasmanian; and other States Injustice. This not Australia.

God Damn perverts of justice and paedophiles. This where the strongest corruption across the board is protecting the paedophile network as has been proved at the highest level.

Michael Phelan, do your mob protect paedophiles? Tough guys,guns and guns.

Hey Rodger, do not give up. It is happening. The snow ball is rolling, changes will happen before Armageddon, (Armageddon is not Global Nuclear War),

But if changes around the globe, for Justice do not occur; Armageddon will take place, but there maybe a few nuclear strikes. Ask Putin and Xi Jinping.

Australia, fight the fight, don’t give up, it is up to you and me and Andrew and everybody contributing and Eve Ash and voters; it is up to us to Stand Against Injustice in Australia; ENOUGH IS ENOUGH.

Hi Andrew

The Appeal process seems to me to be a waste of everyone’s time.

If the Appeal process is restricted to only new evidence it is doomed to failure.

I have completely lost confidence in obtaining justice in any Australian court.

My loss of confidence began in 2018 when I found out about the conviction of Sue Neill-Fraser.