Andrew L. Urban.

Can we trust a criminal justice system that despite some five decades of complaints and dozens of miscarriages of justice, has failed to address the dangers of poor quality scientific evidence or help improve its reliability. If it were an airline, it would be grounded.

When Robert Xie turned off his computer at 2am that July night in 2009 and went to bed next to his wife, Kathy Lin, it was the end of his life as he knew it. Not that he knew it then. Next morning, Kathy’s brother’s family of five was found savagely bashed to death in their home 200 metres away. Robert was eventually charged and, four trials later, convicted of the murders and jailed for life. That conviction and the life sentence hang on disputed scientific testimony concerning the source/sources of the DNA that the prosecution claimed was the evidence that proved Robert guilty. The DNA testimony was so complicated, tortuous and incomprehensible to the court, not to mention the average person (including me and no doubt the jury), that it took up almost the entire week of the appeal against the conviction in early 2020 (decision pending).

In written submissions before the three Appeal Court judges, the appeal stated “the process of explaining the problems with Dr (Mark) Perlin’s (DNA related) evidence is a gruelling and tedious one”. The issues could not be addressed “very quickly and easily”, but unless courts were to simply defer to experts when the material is not readily understandable, it needed to be undertaken.

200 metres from crime scene

Robert Xie

The issue was absolutely crucial, because there was no direct evidence against Robert. The DNA was found in a tiny slick of matter (Luminol testing showed up no blood) on the floor of his garage, where the two families often played, 200 metres from the crime scene. The prosecution had nothing else with which to solve the crime, claiming the deposit contained DNA from the victims and Robert. Frankly, that’s a huge stretch but the prosecution succeeded in convincing 11 of the 12 jury in the fourth trial in 2017 – eight years after the murders.

DNA ISSUES & THE CLAREMONT KILLER CASE

Dr Perlin (see above) is the champion of his own TrueAllele method, an opaque and secretive process sold by his Cybergenetics company but which is as controversial as the LCN DNA analysis method used in the Bradley Robert Edwards trial – see below. TrueAllele had been the subject of peer review in two studies, according to one court – but the court failed to note that both had been authored by Perlin and his colleagues, according to the Harvard Journal of Law & Technology. (Perlin is also a musician who has written songs about catching criminals through his software.)

The Claremont Serial Killer case (95 day trial, November 25, 2019 to June 25, 2020), with confessed rapist Bradley Robert Edwards, 51, convicted of two of the three murders of which he was accused (Jane Rimmer in 1996 & Ciara Glennon in 1997), is the latest to throw into sharp relief the importance of universally accepted, reliable scientific testimony.

Justice Hall in his remarks when sentencing Edwards to life, (September 24, 2020) referred to the fingernail scrapings as the source of the DNA implicating Edwards. The defence had argued (unsuccessfully as it turned out) to discredit the DNA evidence, saying “that the material analysed was not fingernail scrapings but clippings. These clippings were taken as part of the post-mortem examination procedure. That part was not video recorded as other parts of the examination were. Further there was difficulty obtaining a sample of one of the nails (AJM40) because it was close to the quick; AJM40 was initially assessed by PathWest scientists as being debris that was not suitable for testing; that assessment occurred in the context of PathWest carrying out Low Copy Number testing of other exhibits in 2003, testing that was carried out despite the laboratory not being accredited to do that type of testing; when the relevant samples were sent to FSS in the UK in 2008 the samples were prepared for testing by a scientist who no longer has any memory of what he did. He is only able to refer to what he is likely to have done by reference to usual procedures; the DNA in question is trace DNA which was collected and stored in the 1990s when the state of knowledge and the protocols in handling such samples were much less sophisticated than was later the case; and there is a possibility of cross-contamination with other exhibits that did have the accused’s DNA on them.

Further, fingernail samples from Jane Rimmer identified as RH33 and 34 were found and combined and analysed at Cellmark in 2017 or 2018. A mixed DNA profile was obtained; the major component of which matched Ms Rimmer’s profile. The minor component was subjected to Y chromosome analysis and was found to be consistent with the profile of a male PathWest scientist, although there was no documentation that this scientist had been involved in processing these exhibits.

The explanation is that the layout of the examination area at the time of processing would have allowed for the scientist in question to be in the vicinity of the items during examination and processing and therefore represents a possible source of contamination; and (d) a swab from a branch located on top of Jane Rimmer’s body was examined in 2002 and given exhibit number RH21. This yielded a partial profile that was later found to match the profile of a victim of a completely unrelated crime.

Samples relating to that unrelated victim were processed in the laboratory some days either side of this sample. PathWest reached a conclusion in 2007 that this was not a finding of evidentiary value; but in 2009 the exhibit was still being considered, though rejected for possible further testing.

highly controversial

The Low Copy Number (LCN) method of DNA analysis is highly controversial. For example, Police Professional reported “As the sample sizes are so tiny, the risk of contamination is widely recognised to be extremely high.”

And Forensic Genetics Policy Initiative reported that “Judges around the world are involved in a debate over whether a technique known as Low-Copy Number DNA analysis or high-sensitivity analysis, a type of DNA analysis involving the amplification of genetic material, is reliable enough to convict someone of a crime.”

Brooklyn Supreme Court Judge Mark Dwyer even refused to allow the results of LCN DNA testing to be used in a felony case brought by prosecutors.

“To have a technique that is so controversial that the community of scientists who are experts in the field can’t agree on it and then to throw it in front of a lay jury and expect them to be able to make sense of it, is just the opposite of what the `Frye standard` [a test to determine the admissibility of scientific evidence in US courts] is all about,” Justice Dwyer said.

Exactly. Given that absence of reasonable doubt is the test for a guilty verdict, it is imperative that juries (and judges) have confidence in the integrity of all evidence presented to them.

SCIENTIFIC METHODOLOGY FOUND WANTING

The unreliability of scientific/forensic/expert evidence (see example above) is a systemic problem, and not just in Australia. Take a look at Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward, a 2009 report (nothing much has changed since) undertaken by the National Academy of Sciences as commissioned by the U.S. National Research Council (NRC) which applies to all countries, including Australia. The multidisciplinary committee that wrote the report was composed of forensic scientists, statisticians, law professors, biologists, a chemist, an engineer, computer scientists, a medical examiner, and was chaired by Judge Harry T Edwards.

Edwards concluded that “I simply assumed, as I suspect many of my judicial colleagues do, that forensic science disciplines typically are well-grounded in scientific methodology and that crime laboratories and forensic science practitioners follow proven practices that ensure the validity and reliability of forensic evidence offered in court. I was surprisingly mistaken…” The Report observed that `some forensic science disciplines are supported by little rigorous systematic research to validate the discipline’s basic premises and techniques.’

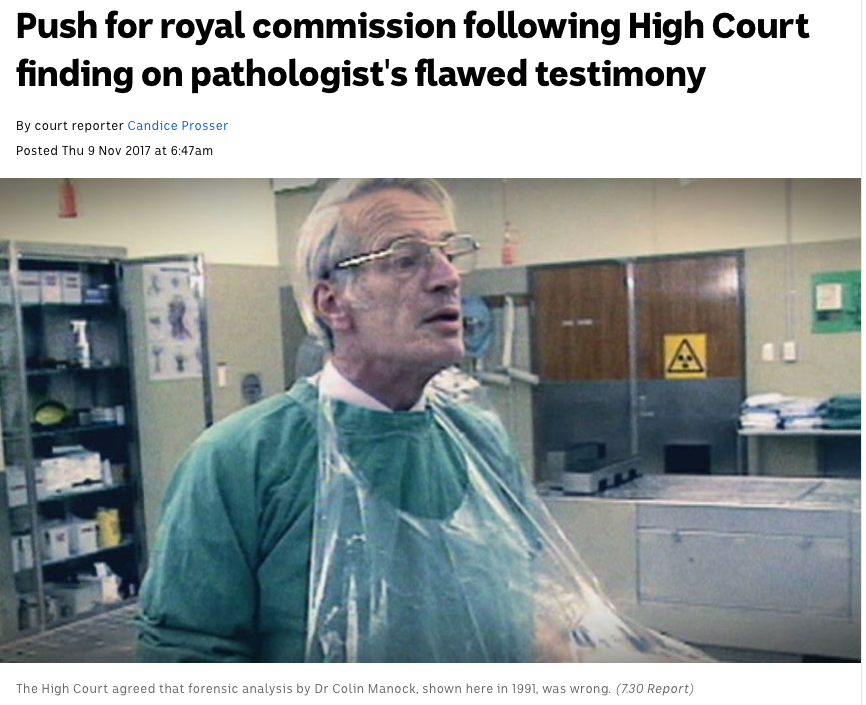

Nothing demonstrates the enormity of the problem of an absence of scientific methodology than the chronic, long term failure of the South Australian legal system to ensure that its Chief Forensic Pathologist was suitably qualified to give evidence. His forensic reports have infected some 400 criminal convictions, the largest volume of potential wrongful convictions generated by a single pathologist in a single jurisdiction in history.

The Chief Forensic Pathologist in South Australia, Dr Colin Manock, was at all relevant times “unprofessional, incompetent, untrustworthy” according to documents lodged with the Supreme Court of South Australia. Dr Manock gave ‘expert’ evidence in some 400 criminal trials over his 26 year tenure. Everyone knew, nobody stopped him.

The Chief Forensic Pathologist in South Australia, Dr Colin Manock, was at all relevant times “unprofessional, incompetent, untrustworthy” according to documents lodged with the Supreme Court of South Australia. Dr Manock gave ‘expert’ evidence in some 400 criminal trials over his 26 year tenure. Everyone knew, nobody stopped him.

One of his many deadly errors was in the case of the drowning murder of 15-year-old Deborah Leach, whose partially clothed body was found buried in seaweed at Taperoo beach in Adelaide’s north-west in 1971. Her convicted killer, Frits Van Beelen, (now in his 70s) admitted being on the mostly deserted beach that afternoon, but has always maintained his innocence of the murder.

Among other evidence, Manock’s testimony as to the time of death formed a significant part of the prosecution case against him. Manock estimated the time of her drowning based on “unscientific” analysis of the teenager’s stomach contents, and testified that it could have been no later than 4:30pm when Van Beelen had left the beach.

In a unanimous decision, the High Court has nevertheless dismissed his desperate 2017 appeal. But Van Beelen’s barrister, Kevin Borick QC, said a new witness had come forward, which could prove Van Beelen’s innocence in a subsequent appeal.

“[The fresh evidence] is a man who saw a girl who was Deborah Leach, on the beach at 4:45pm, which couldn’t be possible if the prosecution’s case is right.”

THE BABY DEATHS

Another catastrophic failure of justice his work caused are the death certificates of three babies he said died of bronchitis; they were bashed to death. Then, after that debacle was uncovered by the Coroner, the Coroner kept the matter to himself as it was the eve of Henry Keogh’s trial (didn’t want to let his findings impact on Manock’s appearance at trial, would you believe), where it was Manock’s evidence that would convince the jury he murdered his girlfriend. Manock claimed this was proven by the grip marks on her leg, where he held her while she drowned in the bath.

Henry Keogh

That took away 20 years of Keogh’s life, until Manock’s rubbish testimony was ripped up by a real scientist.

It wasn’t DNA but a preposterous gymnastic theory of an ‘expert’ that the prosecution took to the jury on the Gordon Wood murder trial. Wood was convicted in 2008 of the murder of Caroline Byrne, whose body was found early morning on June 8, 1995, on the rocks at The Gap, a notorious suicide spot on Sydney’s Eastern coast. In 2012 the Court of Criminal Appeal set aside his conviction and entered a verdict of acquittal. The Chief Justice made it clear in his judgement that even the most basic elements of the case had failed to be established. “I am not persuaded that Wood was at The Gap at the relevant time.” He concluded that the verdict of the jury could not be supported having regard to the evidence.

The judge didn’t even have to bother about the ridiculous gymnastics evidence, in which ‘expert evidence’ from Assoc. Professor Rod Cross, who co-operated with the police, mocked up a scenario in which Wood could have lifted Byrne onto his shoulders and threw her like a javelin off The Gap in the dark night. Despite elaborate experiments at swimming pools to suggest that Wood was possibly physically capable of it, neither Cross nor the prosecution managed to prove that Gordon Wood actually did it.

In a tragic reversal of the exculpatory value of DNA, then Tasmanian DPP Tim Ellis SC dismissed DNA evidence from the crime scene as a red herring when prosecuting Sue Neill-Fraser for the 2009 murder of her partner on their yacht, Four Winds. The DNA found on the deck was matched to homeless then 15 year old Meaghan Vass, but Ellis convinced the jury that the deposit was probably transferred on some cop’s boot and not to worry about it. It was the only solid evidence in that circumstantial case. A decade later, Vass publicly acknowledged that she was indeed on board, with two male friends who were looking for items of value. It was her DNA. Her ‘confession’ was public: on 60 Minutes (Channel 9). Neill-Fraser is still in jail, awaiting a new appeal.

LEARNT NOTHING

There are hundreds of inmates in prisons across Australia who have been wrongfully convicted of a serious crime, such as murder or sexual assault. Estimates range from about 400 to some 650 at any one time, not a large enough number to stir political will, not even considering the massive cost of trials that lead to such catastrophic failures. It will take public sentiment to motivate The System itself to seek reforms to reduce the number of wrongful convictions, as former High Court judge Michael Kirby believes.

As at mid 2019 in Australia, there were just over 9,800 inmates convicted of homicide or similar crimes, robbery & extortion, and sexual assault – but excluding drug offences (ABS). Civil Liberties Australia has estimated that about 6-7% of those incarcerated are wrongfully convicted.

Kirby says: “What is it about our country that always sees us limping behind [UK, NZ and Canada] where justice is at stake,” and believes “we need a better system for reviewing convictions said to have been a miscarriage of justice. Public pressure is the most likely way to prompt reform.”

The criminal justice system seems to have learnt nothing. Almost 40 years ago, a forensic scientist gave testimony that she found foetal blood under the dash of the Chamberlain family car. Azaria’s, obviously. It turned out – much too late – to have been sound deadener. But it took years to correct the ‘scientific evidence’.

38 years in jail

Four years after that dingo took Lindy’s baby in the Northern Territory, Derek Bromley in Adelaide was convicted of drowning a man with the help of eye witness evidence: that of a schizophrenic whose testimony was presented to the jury as reliable. But it isn’t just the eye witness testimony that is disputed. The case was another Manock special, a misdiagnosis of drowning and associated injuries, which at his latest appeal in 2018 was shown by both defence AND crown experts to be totally wrong. In a bizarre and incomprehensible decision, according to legal academics Dr Bob Moles and Bibi Sangha of Flinders University, the appeal court effectively put aside both these reports and against all precedent refused the appeal. He is still in jail, refusing to admit guilt and thus refused parole, after 38 years.

Appeal courts, as we have shown, also bear responsibility for poor decisions in cases where scientific evidence had played a big role; Van Beelen, Neill-Fraser, Bromley, Chamberlain, Keogh, among others not mentioned here … Robert Xie’s appeal decision is yet to come. And that case – five brutal murders of a family – presents the most dramatic example of the importance of reliable scientific evidence. The prosecution presented a weak and circumstantial case – supported only by a threadbare and contested DNA deposit 200 metres from the crime scene.

GUILTY

Evidently, decades of disastrous mistakes and wrongful convictions have not convinced the practitioners of our criminal justice system of the need to ensure, in the words of Justice Harry Edwards “that crime laboratories and forensic science practitioners follow proven practices that ensure the validity and reliability of forensic evidence offered in court.” Verdict: Guilty.

Andrew, you may be aware that expert opinion regarding gastric emptying was provided by Adelaide’s Professor Michael Horowitz in both the Van Beelen appeal and the fourth trial of Robert Xie. In the High Court Appeal he pointed out that back in 1971 the science of gastric emptying was unable to pinpoint any time of death to within one hour. This fact does not seem to have swayed the opinion of the appeal judges, for whatever reason.

In the Xie case, using police assumptions regarding meal size, Professor Horowitz was able to apply modern science and knowledge of residual stomach contents to estimate a time of death very close to 3am in the case of Min Lin. His calculations are quite transparent.

The professor was not asked to estimate a time of death for the children despite data being available. If we do the calculations ourselves, using his methodology, we find that the children died prior to 1:30am. This comes as something of a surprise because Mr Xie is known to have been at his home at this time, and for hours prior. There must be more here than meets the eye.

Harking back to the Van Beelen appeal, judges and jurors don’t appear to be taking everything into account. The jurors in the Xie case didn’t even get a chance as it turns out. The Crown and Defence, by mutual agreement, decided to withhold Professor Horowitz’ calculations and background explanations from the jury! (As we see in the comment of juror 13 (Robert Xie – an evidence-free conviction) “this should have come out, but we heard nothing”.)

Poor Professor Horowitz must be tearing his hair out. He provides all this expert information and it ends up being ignored!

Yes, thanks Phillip. An extraordinary crime demands extraordinarily robust evidence. You highlight one of the crucial failures of our criminal justice system, echoing the thrust of the article. The public needs to know …

Fantastic summary Andrew. I hope to borrow from it from time to time. Very well argued and outlined. When you put all these ‘cases’ ( read victims) together a very concerning pattern emerges of widespread injustices based on dodgy forensics and the criminal justice system’s reliance on ‘experts’ and the CSI Factor. Great article.

Thanks Robin – feel free to borrow…

Robin, frankly I see it as manipulation of the system in order to gain a conviction.

Police & prosecutors know what they can ‘get away with’, whilst remaining inside the boundary, yet appearing to going close to the ropes. We on the outside see that there are times when the boundaries are exceeded.

Was it not ever thus?

While Australian states continue to recruit from the lowest skilled, educated, and psychologically challenged, to fill ranks within our nations policing forces, the undermining of our legal and judicial system is a given. Near daily we are reading, or hearing of reports of venality and criminal practices in the mainstream flow of news services. Combine those factors with the pitiable act of including dysfunctionalism in in house promotions as a form of credibility, and the formulae for ongoing implausibility is cemented. A disintegration of links to past recruiting, training, and improper policing practices needs to be activated before any rejuvenation in faith of the legal and judiciary systems to be professional, honest, or impartial will be achieved. Every state Police Force in our nation, along with our Federal Police have been active agents in devaluing and regressing Australian community values, and it originates with recruiting and training. The problem is of tens of decades old, and many of those who have served within the ranks knew full well of the continuing cultures (and accepted them while being paid), and I believe they are as responsible as illicit drug users for maintaining the generational chains of illegal networks, that undermine our legal processes to this day. Trust of an active copper, or ex copper, is but a generalised misnomer of an abstract concept.