Victoria’s highest court has flagged serious concerns about the scientific diagnosis known as “shaken baby syndrome”, which has been used to prosecute and jail a number of young men for child homicide and abuse in recent years, according to an August 20, 2021 report in The Age by Chris Vedelgo.

The Court of Appeal has ordered a hearing into the reliability of the 50-year-old forensic theory as part of an appeal by Jesse Vinaccia, 28, who was jailed in 2019 for killing his girlfriend’s 3½-month-old son.

In a highly unusual move, the court will hear new forensic evidence from three experts who dispute the scientific basis of shaken baby syndrome and how it was used to secure Vinaccia’s conviction. The experts called during the prosecution will also be re-examined. The outcome could have major repercussions nationwide for past convictions for child homicide and assault — as well as child protection proceedings — where experts have relied on the diagnosis as a basis for prosecutions or other action.

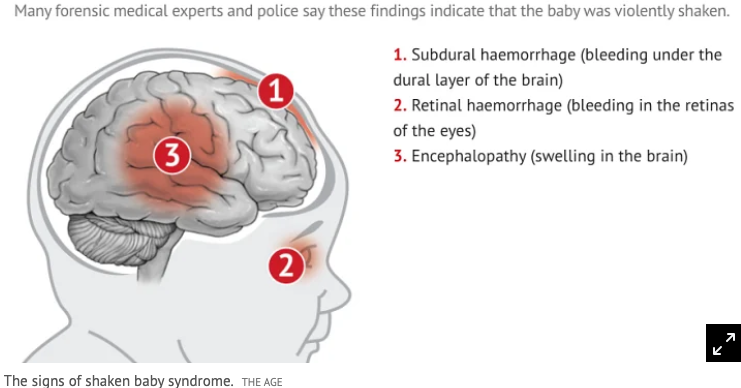

The Age is aware of at least two ongoing criminal prosecutions in Victoria that are now likely to be delayed until the Court of Appeal makes a ruling that might ultimately affect the outcome of those cases. At the centre of the controversy are findings by some forensic experts that an infant must have died as a result of violent shaking if an autopsy reveals a “triad” of internal head injuries – bleeding in the brain, retinal haemorrhage and swelling of the brain – even where there are no external injuries such as bruises, cuts or broken bones or a known history of abuse.

Other scientists say the same symptoms of the triad can be a result of non-violent medical causes, including complications of otherwise silent birth-related head injuries, genetic conditions, infections and bleeding disorders. The “triad-only” diagnosis has become controversial internationally but remains widely accepted by Australian law enforcement, forensic specialists and child-abuse experts.

The issue also raises broader questions about the way scientific evidence is used in courts, with former prosecutors, judges and legal experts saying they are concerned that the use of disputed or untested forensic and medical opinions risks causing miscarriages of justice because of the way juries understand scientific evidence.

In 2020, Vinaccia became the first person to file an appeal challenging his shaken baby syndrome conviction, in part, on the basis the science is fundamentally flawed. Vinaccia had been found guilty of killing his girlfriend’s son, Kaleb, following forensic testimony the baby showed clear signs it had been shaken, even though experts were unable to substantiate exactly how the abuse occurred. The prosecution also relied on statements from Vinaccia that he might have put Kaleb into his cot “pretty rough” and his treatment could have been “a bit bouncy and stuff” as evidence he had shaken the boy. There were no physical signs of abuse apart from the presence of the triad.

“public interest question”

Vinaccia’s appeal claims the confession was unreliable, the conviction was unsupported by medical evidence confirming shaking was the cause of the fatal injuries, and that police and experts failed to consider that the injuries could be accounted for by Kaleb’s pre-existing medical condition, which had previously led to him being hospitalised with swelling in his brain. During an earlier hearing, before the court granted the appeal, Justice Chris Maxwell said that for the Vinaccia case, the “real field of battle is the forensic evidence field” and there was a potential “public interest question” that could be answered about the reliability of the shaken baby theory. “Is this something that the Court of Appeal will have to wrestle with sooner or later, or should wrestle with in the interests of the integrity of the criminal justice system or public confidence in it, or some combination of those things?” Justice Maxwell asked in June.

The green light for the appeal comes after The Age revealed earlier this year that two of Victoria’s top forensic scientists held serious concerns about the reliability of the shaken baby diagnosis and its use in criminal proceedings. The Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine’s deputy director, Professor David Ranson, and the head of the forensic pathology department, Dr Linda Iles, warned that “triad-only” cases were risky because the evidence of abuse was only “indirect” and therefore weak.

“That reliance on a single piece of evidence is always dangerous. Whether you like the triad issues or don’t like the triad issues, it’s not the be-all and the end-all. It behoves the entire legal system to say giving weight and relying solely on a single piece of evidence is incredibly dangerous,” Professor Ranson told The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald in May.

Dr Iles is one of the experts called by the prosecution to testify at Vinaccia’s trial who will now be re-called as part of the Court of Appeal’s review of the evidence. Another is Dr Jo Tully, the deputy director of the Victorian Forensic Paediatric Medical Service at the Royal Children’s and Monash Children’s hospitals, whose evidence has been central to many prosecutions for shaken baby syndrome and child protection actions. She has previously characterised criticism of the evidence for shaken baby syndrome as coming from “non-believers”.

The Court of Appeal also heard that two other appeals against convictions for child homicide and assault have been filed by the same lawyers representing Vinaccia.

Joby Rowe was found guilty of child homicide in 2018 over the death of his three-month-old daughter, Alanah. “Violent shaking with or without impact on a soft surface” was found to be the cause of death based on her internal injuries, with experts testifying there was no other “reasonable explanation”.

Rowe denied mistreating the child. Jesse Harvey was convicted of recklessly causing serious injury to his seven-week-old son, Casey, in 2019. He claimed he did not shake or hit Casey, but said the baby bumped his head on the edge of a couch as Harvey sat down. The medical evidence held the child’s internal injuries were equivalent to a 10-metre fall or high-velocity motor vehicle collision.