Andrew L. Urban.

Before Walkley Award winning journalist and legal historian Evan Whitton died (5 March 1928 – 16 July 2018), I had the good fortune to exchange a few notes with him about miscarriages of justice. He had written the acerbic book, Our Corrupt Legal System, whose title reflects his views about it. So we ask, How would we design a better, fairer legal system?

Would we have the system we have, if we designed it today? From scratch? Could a fairer system avoid or at least greatly minimise the incidence of wrongful convictions? Laws and the legal system are not intended to incarcerate innocent people. Ever. And when it is believed to have happened, the legal system is expected to move quickly to make the necessary correction so the innocent in jail is released. But it doesn’t. Prisoners hardly have the resources and the freedoms to pursue justice for themselves.

Potentially far reaching reforms of our existing system were discussed at the Symposium on Miscarriages of Justice, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Nov. 7 & 8, 2014. (They are included in my book, Murder by the Prosecution [Wilkinson Publishing] and the symposium is reported here).

But reforms will not likely happen, since the profession itself does not stand to benefit. Evan Whitton’s view coincides with that of Professor Fred Rodell, of Yale Law School: “The legal trade, in short, is nothing but a high-class racket.” (from Woe Unto You, Lawyers! (1939).

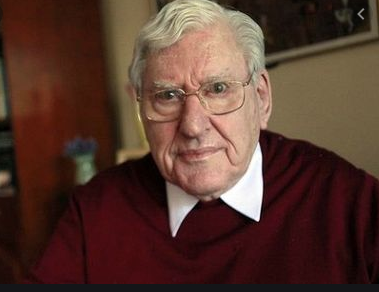

Evan Whitton

To design a fair and effective system which investigates crimes, identifies and fairly prosecutes criminals and puts timely appeals within reach of the wrongly convicted, we have to ignore Rodell and Whitton, and start with the assumption that a better system than we have will remove or at least greatly minimise, miscarriages of justice that put innocent people in jail for years, even decades.

Whitton makes reference to the distinction between our adversarial system – which seeks convictions, and the European investigative system, which seeks the truth and is conducted by trained judges.

This proposed new system applies to the criminal law involving serious crimes and is predicated on the basis that Australia will not abandon its heritage of British law. It will, if adopted, improve the creaking, cobwebbed practices within the existing framework. The objective is to approximate the benefits of the investigative system within our adversarial system … ambitious, I know.

Here are some of the standards that we propose (naive as they may seem to some) for further discussion and refinement, that should apply in building the new, Australian criminal justice system across all jurisdictions, intended to deliver a fairer system without abandoning or dismantling the foundations laid down by the historical British practices.

POLICE INVESTIGATIONS:

POLICE INVESTIGATIONS:

It all starts here. In a paper on miscarriages, legal authors Juliette Langdon and Paul Wilson write: Over-zealous police conduct is recognised as a major contributing factor leading to miscarriages of justice (Anderson 1993; Newbold 2000; Prenzler 2002; Ransley 2002; Wood 2000, 2003), akin to a ‘systemic dynamic’ (Huff et al. 1996:64). As in Wilson’s (1989) paper, over-zealous police investigation was found responsible or partly responsible in 50 per cent of cases. Examples of such conduct include police deliberately distorting a witness’s statement, coercing a confession from a vulnerable suspect, and ignoring exculpating evidence. The issues relating to over-zealous police investigations are similar to those that Wood (2000) described as ‘process corruption’.  Police often appear to engage in such conduct because they strongly believe the suspect is guilty and consequently fail to follow other lines of inquiry. That’s one definition of tunnel vision…

Police often appear to engage in such conduct because they strongly believe the suspect is guilty and consequently fail to follow other lines of inquiry. That’s one definition of tunnel vision…

Their analysis of 32 Australian and New Zealand cases reveals that over-zealous police continues to be a significant factor leading to miscarriages of justice. This factor encompasses a wide range of corruption-related behaviours which may explain why so many cases fall into this category.

NEW STANDARDS

The objective of these standards is to underscore the importance of thorough, professional, unbiased police investigative services that are consistent and reliable.

1) All police officers undergo compulsory training with regular updates and capability assessments: to avoid ‘tunnel vision’, to adhere strictly to investigation procedures, notably accurate record keeping, witness statements, evidence collection; to adhere to a management culture that emphasises serving the court not the prosecution;

2) briefs of evidence to be assessed by a judge prior to passing to the Office of the DPP; (this is a filter to minimise poor briefs crowding the system, reducing the chances of miscarriage as well as potentially saving taxpayers millions of dollars in unnecessary trial costs)

Accountability: as well as the existing perjury provisions, various penalties apply for any breaches of the above requirements, eg failure to adhere to investigation procedures. As the text book Criminal Laws (Federation Press) points out, the effects of many police decisions and practices in the pre-trial process will not be apparent to the defence or the court. It will only be revealed through a royal commission or other official inquiry.

FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, LABORATORIES, PROFESSIONAL BODIES:

FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, LABORATORIES, PROFESSIONAL BODIES:

NEW STANDARDS

The objective of these standards is to minimise the uncertainties and complexities of expert witness evidence; and to better serve the needs of both judge and jury.

A

Forensic services no longer work in tandem with (and close co-operation with) police; they operate under the supervision and control of the Forensic Commission, a statutory body tasked with maintaining high scientific standards, constantly updated with advances in forensic sciences; they also conduct training and professional development.

B

1) All participants in these professions are subject to a system of quality standards, with documented policies and procedures; developed by the respective bodies and relevant advisors/experts;

2) Training is devised to explain evidence in court so that it is understood by juries and judges alike;

3) Strict requirements for validation of evidence are applied and explained in court;

4) Regular training (via Forensic Commission) to avoid contextual bias;

* As Gary Edmond of University of NSW explains, lawyers and courts have not recognised how contextual bias and cognitive processes may distort and undermine the probative value of expert evidence. Courts should attend to the possibility of contextual bias and cross-contamination when admitting and evaluating incriminating expert evidence.

All training emphasis is on serving the court not the police or the prosecution

Accountability: heavy penalties apply for providing misleading evidence to the court whenever this is discovered (& proven) in the post-trial processes

PROSECUTORS:

PROSECUTORS:

NEW STANDARDS

The objective of these standards is to provide prosecutors with barriers to prevent them straying into error.

1) Prosecutors must pass written and oral tests prior to first court appearance (and subsequent refreshers) to ensure adherence to rule of law (e.g. not presenting speculation as fact) and knowledge of prosecutorial ethics & duties;

The tests require prosecutors to demonstrate they can explain forensic evidence rationally and fairly and demonstrate that seeking convictions is subservient to seeking the truth;

2) Prosecutors must undertake a short course on how to work with defendants’ legal representatives post conviction, in cases where a wrongful conviction is a high probability, as determined by an Adjudication panel consisting of one prosecutor, one defence barrister and one judge – see APPEALS G

Accountability: heavy penalties apply for misconduct; professional immunity* is subject to independent adjudication (eg withholding exculpatory evidence, misleading the jury, prejudicial conduct incur heavy penalties, loss of licence)

(It has been suggested by some that prosecutors found guilty of malpractice in securing convictions should be sentenced to serve jail terms that equal those that have been served by the victims of their misconduct.)

* Retired US Federal District Court judge Frederic Block writes how he loses sleep over wrongful convictions – and cites some egregious examples to argue that “Professional prosecutors, charged with the awesome responsibility of faithfully applying the law to guard against innocent people being convicted of crimes they did not commit, should be held accountable,” not protected by professional immunity. He also refers to one case in particular where he “held that the City could be held liable for its misdeeds but I had to dismiss the case against the prosecutor and district attorney on the grounds of prosecutorial immunity. In my decision, I quoted the binding circuit court precedent I was duty-bound to follow.”

DEFENCE

DEFENCE

NEW STANDARDS

The objective of these standards is to provide incentives for excellence in defending clients.

Defence barristers must pass oral and written tests prior to representing any client in court, demonstrating an ability to collate, summarise and present argument in a clear and complete manner to the courts. This process encourages thorough preparation and focuses on performance in court – as distinct from the legal qualifications obtained on theory of the law.

Accountability: Penalties apply when defence lawyers fail to present exculpatory evidence, fail to call key witnesses who have exculpatory testimony, or demonstrate negligence in defending their client.

JUDGES:

JUDGES:

NEW STANDARDS

The objective of these standards is to provide a framework for judges to add new skills to their understanding of the law, to help them manage their courts smoothly, ethically and decisively.

On appointment, judges receive intensive training to understand & manage forensic and other expert witness evidence and to ensure prosecutors adhere to rules of trial behaviour and fairness

Accountability: penalties apply for misconduct (eg, prejudicial conduct, failing to prevent prejudicial conduct by prosecution)

NB Civil Liberties Australia, in its Better Justice campaign, also advocates for reforms, notably the introduction of extra qualifications for magistrates, judges and DPPs; the CLA notes that barristers become judges with no further training. The Better Justice proposals include a review of the 100 year old basic laws, such as the Crimes Act, for improved consistency in bail provisions, sentencing and parole guidelines.

APPEALS:

APPEALS:

NEW STANDARDS

This is the area of the most profound change to the existing (old?) system: no longer bound by the (unstated) restriction in British law that a convicted person only has one appeal, except under newly introduced laws that allow a further appeal … and abandoning the brutal notion of finality, the new STANDARD of appeal is as follows:

A person convicted of a serious crime (murder, manslaughter, rape, sexual assault, child sexual assault, armed robbery, etc) may lodge an appeal and subsequent appeals against the conviction and/or sentence – at any time – if it can be reasonably argued that –

A – there is available new evidence, or evidence that was improperly or misleadingly presented at trial

B – the defence at trial was grossly inadequate, eg failed to present exculpatory evidence, made errors of fact, omitted key facts, etc

C – the prosecution’s conduct at trial was prejudicial; speculation was not supported by evidence; misled the jury

D – the judge erred in directing the jury or came to conclusions not supported by the evidence

E – the sentence is unreasonable with regard to sentences handed down for similar crimes

F – it was not open on the evidence for the judge/ jury to be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that the appellant is guilty as charged

G – where a case has been referred by an Adjudication panel (see Prosecutors 2)

Underlying and supporting these humane grounds of appeal is a critically important process that provides appeal applicants with sufficient resources and access to legal assistance. Recommendations for these would be invited from the relevant bodies in the legal system.

THEN THERE IS THE CCRC …

In an ideal world and one in which this blueprint has been adopted, an Australian version of the UK’s Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) would not be needed (multiple appeals being allowed under this blueprint). But we do not live in such a world … The argument for our own CCRC has been comprehensively made by legal academic Dr Bob Moles of Flinders University. Also the mechanism for it: “A national CCRC can be established by setting up a single CCRC and then each state and territory can legislate to nominate that CCRC as the appropriate agency to review cases on its behalf and exercise powers given to the CCRC by that state to refer matters to the appeal court of that state. This would not involve any constitutional change of any sort.”

In the UK, the CCRC started work in April 1997. In the 22 years between then and April 2019 it referred 664 cases back to the appeal courts; 439 appeals have been successful including around 100 convictions for murder and four in which the poor person had been hanged.

*

This ‘blueprint’ has been drawn up with the benefit of six years observing, researching and writing about wrongful convictions; it is not grounded in formal legal study. We’d love to hear your views on it – please use the reply/comments thread below.

“Heavy penalties.” We call for these when outraged. Yet, arguably, the spirit of an innocence project is one of justice _and_ mercy.

On the practical side, legislation that threatens a powerful group is harder to pass. If passed, it will prevent some misconduct from occurring, but will prevent some misconduct that would have been uncovered, from ever coming to light. The culture may change for the worse: heavy penalties degrade those subject to them and may corrupt those applying them.

How about “mild” penalties? They only need be stronger than the incentives to misconduct, is there a way to weaken the latter instead?

Can we learn from experience — is there a place on Earth where “heavy penalties” apply?

If unsure, err on the side of mercy.

It may help to require all fact-finders to evaluate every indisputable fact of the case as to which story — prosecution or defense — it is more in agreement with, and by how much; and to write that down.

By indisputable fact, I mean things like “witness X claimed Y” , or if even that is in dispute, “witness X gave the testimony he gave while having the demeanor that he had”. At this level, the entirety of what the court saw and heard is a set of indisputable facts. Fact-finders will evaluate each fact, or at least each that either side cares about. This should help them avoid cognitive biases and logical fallacies, and will inform appeal courts.

Example: Amanda Knox caresses her boyfriend soon after her housemate’s murder; carelessly enough to be seen or caught on camera. Gut reaction: this shows guilt, she’s not saddened by the death. But, upon reflection: what proportion of innocent suspects would be so indiscreet? What proportion of guilty ones would? The guilty ones might not mourn the death, but surely they will try to put up an act? If jurors/judges must write it down, they will have to think it through.

Andrew you always pieces that challenge my thoughts and this one is so good. It is past time that change needs to be brought in and I like pretty much all that you have outlined here. It would assist in bringing back a fair system and hold those accountable for their actions or lack of. The training is an essential component in all areas as gaining a piece of paper to say you are qualified is a long way from showing you are competent. This needs to be ongoing training not simply a one off. Now the massive issue – how do we start this process when those working in the system would be oppositional from the start???? I say bring it on as I am sure many people would be fully supportive.

To make a start, public pressure on all politicians, media pressure will follow.

Yes Diane, just like certain professions that demand on going training, not a reliance on qualifications gained in years gone by.

Of course legal practitioners in most disciplines undergo regular training to meet professional development targets as designated by the Law Institute in whatever State/Territory they are authorised in to practice. Often it is a points system, however the major firms generally create their own measures, essentially to weed out those that are unlikely to meet the firm’s billing objectives. In other words, the Prosecution lawyers are in most cases not on the radar of the major firms to poach, unless that they have “connections”.

Andrew has pointed out in previous articles that poverty is a significant factor in wrongful convictions. His article above does nothing to dispel that allegation, but reading between the lines it is not just the quantum of money, but rather it is how it allocated, and importantly by whom.

Yes to all said earlier by LB. I also embrace all your suggestions, Andrew, but achieving change generally in the legal community (note I deliberately didn’t say ‘profession’), would be a bit like trying to convert a tractor into a racing car! They are so entrenched in tradition, as well illustrated by the SNF case (and many others). Geoffrey Robertson QC once told me that in our adversarial system the side that ‘wins’ has the best liar, not the best lawyer! A bit harsh to all the lawyers trying to do the right thing within the existing system, to which I never refer to as the ‘justice system’, but rather, the legal #ystem. A very important distinction! But his observation, in my experience, is spot on.

Lots of good ideas there Andrew… these issues all need discussion. There is a lot of improvement needed but as you say, a lot of inertia in the system.

One issue I think is important is far greater transparency and accountability at every level. Make court transcripts and expert reports public. Allow them to be scrutinized and criticized. Allow the performance of all the people involved including the lawyers and the experts giving testimony to be scrutinized and criticized. Only through transparency and scrutiny will the legal system learn from its mistakes.

You make good points Chris. Transparency is crucial – I would add access to police investigation logs. Easy access to court transcripts is absolutely essential and not at exorbitant cost. Taxpayers already pay for the courts, the stenographers, judges, prosecution, etc. But how to overcome that inertia?

Ha, the big question… inertia!!??

Indeed identifying problems and even their solutions is not the hard part, as so many have been identified in the literature and indeed implemented in various jurisdictions world wide. For example, there are some very effective “conviction integrity units”, similar to the Criminal Review Commissions, within certain U.S. counties… certainly enough for us to have a pretty good idea what works. Overcoming inertia is definitely the hard part!

Persistence, I guess, is what we are all going to need :)

Andrew – any reforms that have the potential to minimise the occurrence of miscarriages of justice surely would be embraced by the professions and the general public? Why would they not be supported is the question? I believe that the vast majority of the general public are not wholly aware of the flaws and the rates of errors that result in such tragic cases as Susan Neill Fraser’s. The general public trusts professionals, including lawyers, and so they should be able to. People are horrified to hear that the SNF case is still ongoing, they cannot understand the errors, the delays and simply “why has nobody in government stepped in and righted this apparent wrong?” This is especially worriesome when calls for urgent reviews have fallen on deaf ears by the Tasmanian Premier, Governor, Attorney General, Police Commissioner et al. Yes, miscarriages of justice have occurred in other states, so before being accused of “Tasmania bashing” everyone take a close look at how other states have handled similar MOJ’s and if we can learn from those and what can be improved to assist in every state. Surely this is a fundamental responsibility of the legal practitioners, courts and governments? If it isn’t then it should be. It is my view that Tasmania’s isolation is somehow assisting this apparently wrongful conviction, one that has been identified by legal experts, not by amateurs, to simply fester. A case of “out of sight out of mind?” If we fail to correct miscarriages of justice when they occur then we fail in the fundamentals of human rights. I think most people would be shocked to see this case occurring in Australia, the nation of the “fair go” where our way of life is revered around the world. Time to step up – it seems we have work to do in living up to this claim and the basic tenets of truth and justice in our courts might be a good place to start. Again thank you Andrew for providing another well written and thought provoking piece.