Recent events in Australia give little cause for optimism that we have either a clean, efficient and effective criminal justice system or an incorruptible and just policing regime, writes DR AUGUSTO ZIMMERMAN in Quadrant (3/1/21), as he deconstructs the appalling travesty of the John Fleming case in South Australia. And sees “something rotten with Australian justice more broadly”.

“The Fleming case shows above all else that Australia’s justice system deficits are by no means confined to Victoria. It reveals that there is something rotten with the state of South Australian justice, and, indeed, with Australian justice more broadly,” he writes. We concur. Just look through our reports….

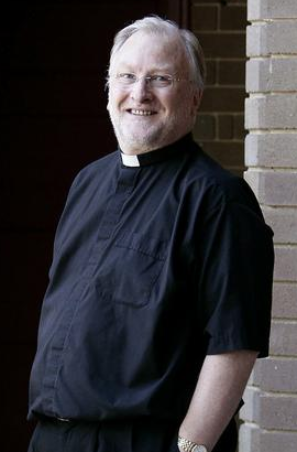

As Zimmerman outlines, “John Fleming is a Catholic priest living in retirement in South Australia. He was initially a married Anglican priest. He has a family. He is a widely published scholar with an international reputation in the field of bioethics. He has been an eminent media commentator in his home state of South Australia. He was the inaugural President of Campion College, Australia’s highly regarded liberal arts institution in Sydney. The appointment to Campion bespoke the esteem in which Father Fleming was held: a respected priest and academic of unblemished character.”

As Zimmerman outlines, “John Fleming is a Catholic priest living in retirement in South Australia. He was initially a married Anglican priest. He has a family. He is a widely published scholar with an international reputation in the field of bioethics. He has been an eminent media commentator in his home state of South Australia. He was the inaugural President of Campion College, Australia’s highly regarded liberal arts institution in Sydney. The appointment to Campion bespoke the esteem in which Father Fleming was held: a respected priest and academic of unblemished character.”

In brief: “His career, reputation, financial security and family life were all but destroyed when, in 2008, the local Adelaide paper (the Sunday Mail, the stablemate of the Advertiser) ran a series of unsubstantiated allegations made by a journalist, Nigel Hunt, against John Fleming of the historic sexual abuse of a minor. These allegations had been previously examined and dismissed by the police in South Australia, casting extreme doubt on their veracity. There were other allegations made, but the claim by witness “Jane” was the most serious, as it alleged the criminal sexual abuse of a minor.”

Zimmerman takes a legal baseball bat to “the manifest legal shortcomings of the judgment of His Honour Malcolm Gray of the South Australian Supreme Court in the initial Fleming case, shortcomings repeated in Fleming’s subsequent appeal to the full South Australian Supreme Court, and finally in the refusal by the High Court to entertain Fleming’s legal arguments in his final appeal. The High Court refused with no explanation, a refusal seemingly based on the assumption that the Fleming application for leave to appeal did not raise any questions of general importance, that is, unsettled matters of law. With the greatest respect to the High Court, this was simply not the case.”

Briginshaw principle crucial

Another baseball bat is wielded by Emeritus Professor of Law David Flint: Arguing the Briginshaw principle, but losing in the lower court, he appealed and lost again in the South Australian Supreme Court in 2016. The Court surprisingly played down Briginshaw, claiming later High Court judgments do not import that presumption into the civil arena and that it was incorrect to raise it to an “onus”, “standard” or “principle”.

Yet in a subsequent case concerning allegations of fraud and not sex abuse, Poniatowska v Channel Seven (2019), the same court applied Briginshaw, restoring it to the status of a “principle”.

As we saw in the Geoffrey Rush case, this principle is crucial for those accused of sexual abuse. But the High Court has twice inexplicably refused to review Fleming and clean up the confusion.

Not to do so leaves the Court open to the criticism that rather than attending to core functions, it is more interested in producing, as they did recently, constitutional interpretations which would have the founders rolling in their graves.

The Melbourne Law Review explains: Briginshaw directs a court to proceed cautiously in a civil case where a serious allegation has been made or the facts are improbable. If the finding is likely to produce grave consequences, the evidence should be of high probative value. The Briginshaw test focuses attention on the standard of the evidence required to prove the case to the ordinary civil standard—it is not a change in the standard of proof. There is no third standard of proof in the common law. More proof means nothing more than better evidence.

Zimmerman is critical that “Judge Malcolm Gray simply preferred the uncorroborated narrative offered by complainant “Jane”, often in the face of evidence that powerfully contradicted Jane’s version of events. Perhaps Gray was simply swept up in the emerging ideology of “always believe the victim”.

“Second, the judge in the Fleming case failed to give due and proper regard to the difficulties associated with defending allegations as to conduct said to have occurred many years ago, particularly when key witnesses are no longer alive. When the plaintiff becomes defendant, has to, in effect, prove a negative, and has lost over time access to potential exculpatory witnesses and associated records and evidence, the task of winning a civil action related to an ancient accusation and in the face of a judge overly sympathetic to the complainant’s “narrative” becomes next to impossible.

“The complainant’s contradictory and uncorroborated testimony was anything but compelling, as the trial transcript demonstrates.”

Among several other issues, Zimmerman is also deeply concerned at errors continuing at the appeal, “The appeal judges stated that any prejudice involved in witnesses unable to testify due to death or infirmity should be visited on the appellant. The reason these witnesses were unavailable to testify is the extraordinarily long delay in the complainants making their complaints. This ruling by Vanstone et al was not made on the basis of any stated authorities and may well now become a precedent for other cases. This is outrageous. Why did the High Court not see that this was a matter of law crying out for clarification?”

* Dr Augusto Zimmermann is Professor and Head of Law at Sheridan Institute of Higher Education in Perth, and Professor of Law (Adjunct) at the University of Notre Dame Australia, Sydney campus

* Dr Augusto Zimmermann is Professor and Head of Law at Sheridan Institute of Higher Education in Perth, and Professor of Law (Adjunct) at the University of Notre Dame Australia, Sydney campus

I think history has churned out records of many who, irrespective of a culture of criminality and brutality, when the opportunity arises, they will don any armband in an effort to maintain their desired positions in the role of a cappo Andrew. Decades may well have rolled on from the most recent gross European example, but those willing to play two sides against the middle for gain, are still out there.

It is hardly a unique manifestation to recognise the long term corrupt actions of policing and ex policing forces across Australia for many decades Andrew. Media reports continuously expose the paucity of professionalism among those who make up our active policing forces, across all ranks, spheres of activity, and irrespective of gender. From drunken police women urinating on War Memorials, as in NSW, to the supposed studs in various disguises who are not content with sleeping with each others wives, and shooting each other (as recorded in Victoria), and those examples are before mentioning fundamental practical criminal behaviour from the closing ranks to protect criminals and crime within, to perjury and blatant deceit. Without doubt I concur that the general Australian public has recognised a devaluing of moral and civil standards across all communities due to the accepted cultures of duplicitous and venal behaviour by members, and within policing force organisations. The oath to serve communities means nothing, and the machinations within ensure conformity to the ill gotten status quo, and very few if any, have the intestinal fortitude to confront the sad realities of their corrupted employment.

All of which enhances the value to society of those members of the police who, often despite a culture of incompetence or worse, do an outstanding job and deserve our thanks. They do exist… and they detest bad cops more than you or I.

Give me a break Andrew, accepting the culture and payment for two decades or more then supposedly standing up for justice. More like I think I smell an opportunist and hypocrite .

Please clarify what you mean and who you smell as a hypocrite. It’s not clear what you are referring to?