Andrew L. Urban

In my own narrow lane of writing about wrongful convictions, the concentration of error prone judges probably seems higher than elsewhere in the legal system. But maybe not … Supreme Court judge (since 2014) Belinda Rigg SC, defied the assessments of police and the NSW Premier to permit the march across the Sydney Harbour Bridge on Sunday August 3.* It wasn’t her first misjudgement … [see Addendum]

I observed Belinda Rigg SC in June 2020 in action when she was Senior Public Defender acting for Robert Xie at his appeal against the (wrongful, we say) murder convictions of five of his wife’s family. It was a train wreck; the appeal was dismissed. Not only did Rigg ignore her client’s well-informed instructions, she made serious errors of judgement in arguing her case in front of the three judges on the bench. Not that they distinguished themselves, either.

As I reported at the time:

Of the eight grounds of appeal, the first three concern the DNA evidence which was always problematic, a tiny sample found on the Xie house garage floor, 200 – 300 metres from the crime scene: the Lin family home, both in Epping, Sydney.

Rigg began by advising the court that the argument over the DNA evidence will take all week, with the last two days devoted to expert witness testimony. Dr Mark Perlin’s expert testimony on the complexity of the DNA material will come under scrutiny, and Rigg foreshadowed it will be shown to be unreliable in fact and badly presented to boot. Dr Perlin “went beyond his expertise” she told the court, giving evidence that was “misleading, confusing and unfairly prejudicial”.

Then Rigg stated what should have been the crux of the DNA evidence: that “expert evidence is silent on the timing of the deposit, or on how it came to be on the garage floor.” (emphasis added)

Those two pieces of crucial information were missing from the trial.

The DNA argy-bargy was sleight of hand at trial and at the appeal. The strongest – and I argue the only ground – should have been Xie’s alibi, which trumps the entire prosecution case. It was so deadly to their case they tried to negative it, from the police to the court. I deconstruct this unethical attempt, which fooled the judge & jury (along with my critique of the appeal judges) in my book FRAMED – how the legal system framed Robert Xie for the Lin Family Murders

And before Rigg got her hands on this case at appeal, the trial judge, Elizabeth Fullerton, mangled the trial in a way that resulted in the guilty verdict.

During her summing up, Her Honour repeatedly gave the alibi directions with the embedded timeframe that the murders were committed after 2:00am – as the Crown alleged, without proof.

To support that allegation the Crown claimed Robert Xie had sedated his wife so he could leave their bed and commit the murders. This absurd allegation was not supported by any evidence – and is the most despicable fabrication in the seeking of a conviction.

“While I consider it very likely that the offender sedated his wife, I am unable to be satisfied of that fact beyond reasonable doubt.” In that case, why did she not direct the jury to return a not guilty verdict?

A famous counsel regarded as one of the most successful at arguing in front of the High Court examined the case and found ample grounds for appeal.

Appeals to the High Court are about errors at law. Here is an excerpt from what this counsel would argue:

The trial judge’s “CSI” direction in overall effect encouraged the jury to disregard any doubts about or gaps in the crime scene evidence because the trial was taking place in nthe “real world” and not the world of “TV fiction”.

Such directions were irrevocably subversive of a fair trial. They undermined the standard of proof and involved the judge intruding into the jury’s task. The case against the applicant was largely circumstantial, and questions of inference from observations at the crime scene, and possible alternative explanations, were central to the case and the jury’s task. The impugned directions were remarkable and provoked defence counsel to seek a discharge of the jury.

What the trial judge seems to have been telling the jury, emphatically and withreference to her personal experience and opinions, was that gaps in, or problems with the crime scene evidence could be minimised or put aside. Her Honour did not explain what the “CSI effect” was, referring to unidentified studies by unidentified academic experts. The jury were given to understand that the directions were standard directions which had an authoritative foundation, but this was not so.

The directions were novel, it is submitted, and at odds with fundamental precepts of the criminal law concerning onus and standard of proof.

Rigg and Fullerton are by no means alone on the naughty bench. I’ll provide some snapshots of instances I have come across.

Alan Blow – retired Chief Justice of Tasmania

This was my first case in following what I consider to be wrongful convictions, based on the transcripts and other material available. Blow was the judge at the 2010 Sue Neill-Fraser trial; here are some of my concerns, with extracts from his sentencing remarks. In effect, Blow was following the prosecution’s speculative arguments.

Blow: I cannot rule out the possibility that the attack left him deeply unconscious, and that drowning was the cause of death

Urban: Baseless speculation based on baseless speculation. The evidence bin was totally empty!

Blow: I am satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that Ms Neill-Fraser used the ropes and winches on the yacht to lift Mr Chappell’s body onto the deck; that she manoeuvred his body into the yacht’s tender; that she attached an old-fashioned fire extinguisher weighing about 14 kilograms to his body; that she travelled away from the Four Winds in the tender with the body for some distance; and that she dumped the body in deep water somewhere in the river.

Urban: On what evidence? None was produced in court.

Blow: … the absence of the fire extinguisher

Urban: The absence of the fire extinguisher does not by itself prove that it was used to weigh the body down and is speculation reliant on the sum total of the prosecution’s speculation; besides, one witness, a mechanic who had worked on the boat, gave evidence that it may not have been on board at the time; another witness (an ex-Wormald employee) said she did not see it on board.

Blow: … the scientific examination of the tender, DNA matching of samples from the blood on the yacht and Luminol positive areas of the tender with Mr Chappell’s DNA

Urban: This is either a confused or a misleading statement, despite the words ‘scientific examination’: a) the presumptive (preliminary) luminol test (for a host of substances including blood) was positive, but the confirmatory test proved there was no blood in the dinghy – not Chappell’s nor anyone else’s; b) Chappell’s DNA being present on his own dinghy is not proof that Neill-Fraser put his body in it.

Blow: …and the evidence that Mr Chappell’s body was not found in the sections of the river searched by police divers

Urban: This is totally unsustainable reasoning; His Honour calls the absence of a body evidence that the accused dumped the body in deep water ‘somewhere’.

Bad judgement followed Neill-Fraser all the way…

Legal errors and mistakes in the majority judges’ reasoning in dismissing Sue Neill-Fraser’s latest appeal against her murder conviction further disgrace Tasmania’s legal system, bringing to six the judges in this case to have contributed to a catastrophic failure of the justice system. (Trial: Blow J; first appeal: Crawford CJ, Tennent & Porter JJ; second appeal; Wood & Pearce JJ)

Reminiscent of dissenting remarks by Justice Weinberg in the Pell appeal, which was echoed by the High Court 7 – 0 in Pell’s favour, Justice Estcourt’s dissenting remarks in the Sue Neill-Fraser appeal put him at odds with his two fellow justices on the bench. So did Weinberg’s. Just goes to show, it’s not the quantity but the quality of appeal decisions that matter. (In Pell’s case two Victorian appeal judges got it wrong …)

Early in the reasons for judgement (par 56 of 544), Justice Wood refers to the appeal judges having “consideration of the transcript of the evidence at the trial and also exhibits tendered on the trial, and the view of the scene that was undertaken by the jury on the first day of the trial.” The jury in Sue Neill-Fraser’s trial did not go on board the Four Winds (see page 2 of the transcript). They should have, of course.

Adams JA

In the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal, Adams JA said: “… the evidence of the Complainant … was not so persuasive as to dispel the significant doubts raised by a number of seeming implausibilities and inconsistencies…” yet went on to refuse the appeal. Significant doubt is surely more than reasonable doubt?

In the same case, one of the four broad grounds of appeal contained in the 76 page petition (ignored by the NSW Attorney-General) showed “Serious shortcomings in the summing up given by His Honour the Judge (now deceased), including that the applicant had made “admissions … which is totally incorrect.”

Gageler, Gleeson, and Jagot

The High Court judges who heard Derek Bromley’s appeal in 2023 were Chief Justice Stephen Gageler, Justice Jacqueline Gleeson, Justice Jayne Jagot, Justice James Edelman, and Justice Simon Steward. The majority—Gageler, Gleeson, and Jagot—dismissed the application for special leave to appeal, while the minority, Edelman and Steward, dissented, arguing there was a significant possibility Bromley was innocent and that the appeal should have been allowed due to a substantial miscarriage of justice

Three judges in South Australia’s appeal court “fundamentally failed to pay due regard to the rule of law and to the well-established principles governing criminal appeals,” according to legal academics Dr Bob Moles and Bibi Sangha. “The principles espoused in their decision are not only contrary to established authority but have never before appeared in any legal judgment in Australia, Britain or Canada.”

And to prove that some judges are simply lacking good judgement…

Justice David Mossop of the ACT Supreme Court in April 2024 in Australia made a bad decision in a criminal trial, by sentencing a 93 year old husband to nine years in prison for the mercy killing of Jean, his 92 year old wife, suffering from dementia.

Justice David Mossop said that while the length of any sentence would have little consequence given Morley’s limited life expectancy, only a term of imprisonment would be appropriate. Not callous or anything …

“Murder remains murder, notwithstanding the age or infirmity of the victim,” he said. “The forceful murder of one’s spouse must be denounced. Even in extreme circumstances of age and infirmity … [murder] is not acceptable,” he said. Some may regard that as pompous and insensitive.

He suffocated Jean with a pillow after she came to bed one night, then tried several times to kill himself.

“[This is] a tragic end to the couple’s long and happy life together,” said Mossop.

Yes, thanks to His Honour’s failure to suspend the sentence, which would have been the wiser, more humane and justified decision.

Justice Mossop noted the killing had not been motivated by malice but rather by Morley’s inability to realise there were other ways the pair could live with more support. How ironic that Mossop failed to realise there were other ways Morley could be held accountable under the law, under the circumstances. And besides, does he not know why mens rea (effectively meaning guilty intent) is a crucial aspect of the law? He himself articulated how Mossop’s act was not motivated by malice. Where was the defence?

Morley has previously been given three to six months to live as skin cancers have penetrated his skull.

Justice Michel Lee (Federal Court)

Bruce Lehrmann sued Network Ten and journalist Lisa Wilkinson for defamation over a 2021 broadcast on The Project discussing Brittany Higgins’ sexual assault allegations, which did not name Lehrmann but implied his involvement. Justice Michael Lee dismissed the defamation claim, finding the allegations substantially true on the balance of probabilities.

“Bruce Lehrmann is a rapist! Bruce Lehrmann is a rapist!” twice for good measure, said Justin Quill of the law firm Thomson Geer, who had acted for Network Ten, direct to TV cameras after Justice Lee’s judgement. Lee was not pleased and demanded a transcript before the hearing on costs. Lehrmann has been labelled a rapist in a civil proceeding, just as he would have been had his trial completed and a jury found him guilty beyond reasonable doubt. In other words, to all intents and purposes, he is regarded in the same bad light as a criminal – which he is not. The difference has been blurred. Quill re-emphasised the blurring, saying “how can it be unreasonable to publish something that was true?”

How does this sit with the rule of law? I asked Chris Merritt, vice president of the Rule of Law Institute of Australia:

The remarks by Justin Quill, who is one of this country’s leading media lawyers, have lessons about the catastrophic consequences of using the law of defamation to deal with accusations that are, in essence, criminal in nature.

It inevitably leads to confusion and undermines public confidence in the justice system’s ability to distinguish between guilt and innocence.

Those who assert that the defamation victory by Network Ten and Lisa Wilkinson means Bruce Lehrmann is a rapist can draw support from passages in the judgement of Justice Michael Lee of the Federal Court. But that is not the full story and to treat it as such is unhelpful.

Lehrmann has not been convicted by Justice Lee or anyone else on a criminal charge of rape. Under the criminal law he is not a rapist.

So while a defamation judgement on the lower civil standard of proof has upheld the truth of the imputation that he is a rapist, that is not the case under criminal law.

This will remain so even if Lehrmann loses his appeal in the defamation case. [Due to be heard August 19 – 22, 2025]

The blame for this appalling position rests with the authorities in the ACT who stopped the criminal case against Lehrmann because of what they said was concern for the wellbeing of his accuser, Brittany Higgins.That decision stripped Lehrmann of his right to have the accusation against him tested against the rigours of the criminal law.

Describing Lehrmann as a rapist without explaining the significant differences between defamation and criminal justice – and the failure of the ACT justice system – only adds to confusion and relieves the ACT authorities of the odium that is rightfully theirs.

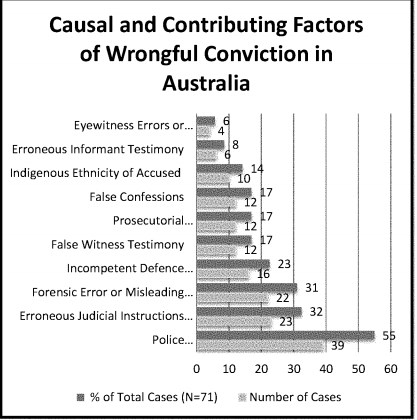

I needn’t go on…you get my point. No surprise, then, that judicial error is a contributing factor in 32% of wrongful convictions, second only to police inputs (at 55%). That, I suggest, reflects badly on judges’ competence at judgement all round.

Griffith University research

*The Harbour Bridge march decision was a political matter, not legal; it was not up to an unelected judge to determine. So her first error of judgement was to agree to take the case.

8/8/2025 ADDENDUM:

In his column in the Australian, “Judge doesn’t deserve criticism for decision to allow Sydney Harbour Bridge protest march” Chris Merritt, Vice President of the Rule of Law Institute, points out that “What happened on the bridge is not the result of judicial activism or bias. It is the result of a flawed permit system for street protests that smoothed the way for a great national icon to be used for propaganda purposes.

It is also curious that there is no sign in Rigg’s judgment that anyone bothered to tell the judge about legal changes in 2022 that protect major facilities.

That new law, Part 4AF of the Crimes Act, imposes criminal penalties on protesters who block access to major facilities.

Part 4AF was inserted into the Crimes Act by an amendment that also changed the Roads Act, which now imposes criminal penalties under section 144G for obstructing major bridges – including the Harbour Bridge.

The judge might have appreciated it if someone had mentioned Roads Act regulation 48 which says: “A person must not, on the Harbour Bridge … conduct or participate in any public assembly or procession.”

Fair enough. But aren’t we warned that ignorance of the law is no excuse?

The fact is in the criminal law domain – probably others like family law, and others, anything outside of purely commercial litigation really – the benches of judiciary are heavily packed with a large supermajority of careerists following government policy. If they cared strongly about the tradition of justice of common law systems they would not have risen above Magistrate level, and even then if that low in the pecking order they’d still probably be hounded out of position. There is no room in the appointment system for those not on program to be appointed – if someone slips through the cracks, the minute she or he applies justice fairly there will be shrieks of anger from the media machine, the outrage machine, and there position will become completely untenable.

The reason I guess it shocks some is they naively believe in an impartial judiciary, or see the judiciary as a check on government power. The fact is, an innocent man accused of a crime he didn’t commit is going to get zero airplay in 99.999% of cases – the only exception I can remember is that prison guard whose ex conspired with an on-duty police officer to frame him for rape, and the media actually went in to bat for him. That’s one case in like 30 years of this crazy-land “paradise” we’ve created in Australia and other similar countries.

The thing with judges is – civil servants run amok and police run amok can only do what they do because those judges do what they do. You could have all the chances that have happened in terms of political appointments in police and civil service and their campaigns, criminal actions, perjuries, etc., and if the criminal law and judges had retained the level of justice and fair play they had in say 1990, it would make hardly any difference to the citizenry – there’d be the odd person convicted of a serious crime due to police planting evidence, but otherwise none of what has happened would have happened. Does that mean judges are to blame? Basically in my view as individuals yes – but they’re people who dropped out of a funnel designed by the wealthy elites, mostly whites, who control these countries political, educational and media systems – at an individual level, yes a psychopath who is unbothered by destroying the lives of dozens of innocent people by sending them to jail for long to life sentences simply to get his or her status and income as a senior judge is a problem – but way bigger of a problem is a system that almost exclusively selects for that kind of person and then puts her or him in a position to destroy countless lives.