Andrew L. Urban

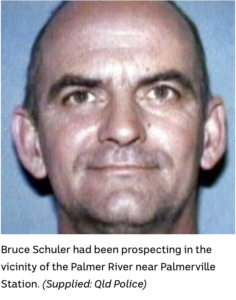

The conviction of Stephen Struber and Dianne Wilson-Struber for the 2012 murder of gold prospector Bruce Schuler in remote Queensland carries a high risk of wrongful conviction when assessed against established international miscarriage-of-justice indicators. Former detective and author Graeme Crowley identifies 140 inconsistencies in the evidence. LIA questions the verdict.

Cannibal Creek runs through the northern part of the Gold Nugget camp site west of the main Palmerville Station campsite in outback Queensland, 300kms NW of Cairns. To say this is remote is an understatement. But for gold prospectors, it’s never too remote. Besides, they’re a hardy bunch.

It was a fine morning on Monday, July 9, 2012, when Bruce Schuler and fellow prospectors Daniel Bidner, Tremain Anderson, Kevin ‘Rusty’ Groth, were trespassing-in-hope on the former gold leasehold property, now farming cattle. At 9.30, the lease holders, Stephen Struber and Dianne Wilson-Struber, thundered up in a Ute and fired off two (or three) shots at them. The group ran for cover. When they emerged, Schuler was missing. Neither his body nor his prospecting equipment have ever been found. The prospectors didn’t call the police until 7.05pm and they never tried to call Bruce Schuler.

It was a fine morning on Monday, July 9, 2012, when Bruce Schuler and fellow prospectors Daniel Bidner, Tremain Anderson, Kevin ‘Rusty’ Groth, were trespassing-in-hope on the former gold leasehold property, now farming cattle. At 9.30, the lease holders, Stephen Struber and Dianne Wilson-Struber, thundered up in a Ute and fired off two (or three) shots at them. The group ran for cover. When they emerged, Schuler was missing. Neither his body nor his prospecting equipment have ever been found. The prospectors didn’t call the police until 7.05pm and they never tried to call Bruce Schuler.

FROM THE CROWLEY INVESTIGATION

These excerpts, a small selection from a long list, provide important context:

Four search warrants were executed and Palmerville Station was searched extensively. There was no forensic evidence linking Dianne Wilson-Struber or Stephen Struber to the crime.

After thirty days of intensive searches, there was no evidence to connect either Dianne Wilson-Struber or Stephen Struber to either of the two crime scenes claimed by the prosecution. No blood, DNA, physical evidence or forensic evidence had been found on their bodies, their clothing, in or on their vehicles, or in their homestead or outbuildings. The listening and tracking devices which policed placed on the Strubers’ home and vehicles did not uncover any incriminating evidence.

Aboriginal police tracker, Barry Port, 70, spent three days and nights searching for any sign of Schuler and stated that, “I could not find any signs to follow. We were looking for boot prints, bits of clothing, his pick, shovel or metal detector, stuff like that.“

Sergeant Frank Falappi, who works closely with Port, said the tracker was impressive to watch…. “It is amazing what he can see in the landscape. He can see human and animal tracks in the bush that are almost impossible for us to make out, even when he shows us up close.”

The prosecution asked the jury to infer that Schuler ran away in fear, carrying a significant number of bulky, loosely held possessions, without dropping a single item or leaving a single trace of forensic evidence.

Crime Scene 2 uncovered approximately 3 small burnt patches of grass on the side of a steep ravine, partially burnt matches, an empty film canister, bailing twine, and only small blood stains on leaves and rocks. One of the partially burnt matches was later found to have Bruce Schuler’s DNA on it, as did the black twine; the blood drop was matched to Schuler’s blood as was the blood on the rocks.

- A partially burnt match was found and tested for DNA. Bruce Schuler’s DNA was identified; no other DNA was identified on or near the match, or anywhere in the surrounding area.

- When questioned by Crowley about this, Detective Sergeant McLeish alleged that the Strubers had Bruce Schuler’s DNA on their hands and transferred it to the match when they lit a fire to burn evidence on the grass, a claim made without evidence.

- Note, the Struber’s DNA was not found on the match or any area surrounding the site, and Bruce Schuler’s DNA was not found on the Strubers, their clothes or any of their property.

The prosecution claimed Schuler had been fatally shot at close range by the .357 magnum handgun that was missing from the homestead. A .357 round can penetrate an engine block. A wound from this firearm would leave a very large exit wound and a large amount of blood, bodily organs, and/or brain matter. None of which was found.

There was no evidence of drag marks, footprints, disturbed earth or anything else you would expect to see when a man and a very small woman drag a ninety-kilogram dead weight onto the tray of a vehicle, as proposed by the prosecution. (An echo of the Sue Neill-Fraser case, in which it was alleged she dragged Bob Chappell’s corpse from below deck to upper deck and then into their dinghy…a near impossible task for anyone, let alone a middle aged woman. There was no evidence to support the allegation.)

None of the prospector’s versions of events aligned in timing, actions, or locations on either the day before, or day of, Schuler’s disappearance.

Bidner and Anderson both had previous criminal convictions at the time of Schuler’s disappearance. Bidner has criminal history dating back to 1984, most recently for cultivating 100 kilograms of cannabis. Anderson has criminal history dating back to 1992, most recently for cultivating 300 kilograms of cannabis. Despite describing as each other as ‘almost family’, they each denied having any knowledge of the others drug related offences.

Bidner told police he had never been on Palmerville Station, when he had been trespassing on Palmerville Station for over 10 years. There is video footage of Bidner on Palmerville Station as recently as one week prior to Schuler’s disappearance.

Bidner did not disclose to police that he had taken video footage during the prospecting trip on the day before and morning of Bruce Schuler’s disappearance – and continued to deny knowledge of a second video even during the trial. These videos called into question timing, actions, and locations of Bidner, Anderson and Groth’s stated movements leading up to Schuler’s disappearance.

No explanation was given by the prospectors as to why they didn’t use Anderson’s satellite phone to call for help immediately, instead, waiting 8-9 hours to contact police to report Schuler was missing. Similarly, they did not attempt to call Schuler’s satellite phone when they could not locate him.

It was never made clear to the jury that the prospectors all heard gunshots they believed to be from varying firearms, even though the prospectors would be considered ‘qualified witnesses’ given their years of experience with firearms.

It was not made clear to the jury that none of the firearms identified by the three prospectors matched the sound made by either of the firearms that were reported to be missing from the Strubers.

The prosecution stated to the jury that the tyre tracks leading to Crime Scene 2 matched the Strubers vehicle, omitting the fact that the tracks were consistent (not a direct match) to the Struber’s other vehicle, not the unregistered ‘bush basher’ with no tray sides that was identified by Anderson and Bidner. Senior Constable Scott Ezard’s evidence stated that ‘This track width was identified to be consistent with the track widths measured on the second Toyota Land Cruiser with the tray sides and hoist crane fitted’.

To account for this discrepancy, the prosecution stated that ‘none of the witnesses pick out which one (referring to the vehicles). “They don’t say whether it’s the registered or the unregistered one.” This is not accurate and clearly misleading. Bidner and Anderson stated on multiple occasions that they saw the unregistered Landcruiser. Bidner specifically referenced that it, ‘has no side gates all round’. This description only applies to the unregistered ‘bush basher’ vehicle.

Stephen Struber stated repeatedly at trial that he was not in the area where Bruce Schuler was last seen on the morning in question, stating, he and his brother Charles were out at the dam. As noted above, the dam is approximately eight kilometres to the south of Palmerville Station.

The calls made at 12:43pm correlate with the neighbour, Bertie (‘Mick’), stating that he saw the Struber’s return home for lunch on the Monday, from the opposite direction of the crime scenes.

The telephone traffic between Stephen Struber and Charles Struber was of evidentiary value. The investigators should have considered that Stephen Struber, and by default Dianne Wilson, had an alibi on Monday 9 July 2012.

Judge Henry, during legal argument in the absence of the jury said, ‘in other words they’ve got concerns that the whole thing hasn’t been the subject of generally truthful evidence then obviously that’s the end of it if they think these prospectors have come up with a story and that shortcuts everything….’

LIA analysis

The following is a report on the case by LIA (Legal Intel AI), the newly refined AI tool specifically trained for legal research and analysis.

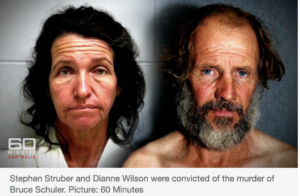

On 24 July 2015, after a two-week trial in the Supreme Court (Cairns), a jury found both Struber and Wilson-Struber (photo at left) guilty of murder, even though no body, no murder weapon and no direct eyewitness to a killing were produced. At sentencing, the judge remarked the case was “cowardly and callous,” and noted the couple had the opportunity to give closure by revealing the location of the remains.

On 24 July 2015, after a two-week trial in the Supreme Court (Cairns), a jury found both Struber and Wilson-Struber (photo at left) guilty of murder, even though no body, no murder weapon and no direct eyewitness to a killing were produced. At sentencing, the judge remarked the case was “cowardly and callous,” and noted the couple had the opportunity to give closure by revealing the location of the remains.

The couple appealed. The appeal (heard 31 May 2016) was rejected by the Queensland Court of Appeal (judgment delivered 11 November 2016). The Court did not accept alternative possible explanations for Schuler’s disappearance proposed by the defence. In 2017 their application for special leave to the High Court was refused.

Defence’s core strategic thesis was that the Crown could not prove:

- that Bruce Schuler was dead,

- that he was murdered,

- that the Strubers were present,

- nor that any forensic or physical evidence tied them to a killing.

Accordingly, the defence argued that the prosecution had merely assembled a narrative based on coincidence, inference, and suspicion, not evidence.

Alternative possible explanations put forward included:

Accident or Misadventure in Remote & Hostile Terrain

Third-Party Offender(s) — Unknown Trespassers or Illegal Prospectors

Mistaken Identification of Vehicles / Sounds / Distances

⁃ No witness could reliably place the Strubers at the scene of a killing.

The Queensland Court of Appeal acknowledged the defence arguments but held:

- the circumstantial evidence was capable of supporting a guilty inference, and

- the jury was entitled to reject the defence alternatives.

Thus, the alternatives were considered but not accepted. Yet each defence alternative explanation remains consistent with the known evidentiary gaps: no body, no weapon, terrain complexity, forensic ambiguities, witness inconsistencies.

After their conviction, Schuler’s family campaigned successfully for the 2017 legislative reform in Queensland — the so-called “No Body, No Parole” regime — making it mandatory for convicted murderers to reveal the location of the victim’s remains before parole. (Our say: Yes, but …)

In his book, Fool’s Gold, retired detective and author Graeme Crowley identifies 140 inconsistencies in the prospectors’ evidence (see above for excerpts). For example, the prospectors gave clear and repeated evidence to police that Struber and Wilson did NOT go to the area designated CS2, where Schuler was ‘executed’. Instead they told police the Ute did a U-turn after leaving CS1 and headed away from the area in the direction it had come. The prosecutor ignored the evidence of his own witnesses and told the jury “it was reasonable to infer” that Struber and Wilson went to CS2. (“reasonable” as it suits the prosecution case…)

From a legal-technical perspective, courts correctly applied circumstantial proof doctrine: criminal law (in Queensland) does not require a body or murder weapon if the circumstantial evidence, taken as a whole, permits a “reasonable inference” of murder beyond reasonable doubt. The 2015 jury verdict, upheld on appeal in 2016, shows that the standard was met in the view of the courts.

Nevertheless — through a risk-of-miscarriage or wrongful-conviction lens — the Struber case exhibits many of the classic risk factors identified in criminal justice research: (1) no direct eyewitness; (2) no body; (3) no murder weapon; (4) heavy reliance on a small number of eyewitnesses whose accounts may have changed; (5) forensic and physical evidence that is circumstantial, degraded, or ambiguous; (6) remote crime scene in rugged terrain; (7) absence of independent corroboration of the prosecution’s narrative (e.g., no drag marks, no items carried away, no ballistic evidence).

Accordingly, while the conviction cannot be automatically overturned — the threshold for a successful appeal remains high — the Crowley-driven re-examination raises legitimate and serious concerns about whether the conviction rests on sufficiently reliable evidence.

What remains disputed or uncertain:

-Whether the forensic evidence (blood, tyre-marks, burnt grass, vehicle damage) was sufficiently robust and reliably linked to the Wilson & Struber. Crowley argues the linking was speculative or improperly handled.

-The reliability of the eyewitness testimony: prospectors’ accounts reportedly shifted over time; also, no one actually saw a shooting or a body.

-Whether alternative explanations (e.g. accidental death, third-party offending, trespasser involvement) were properly investigated or dismissed at trial. Crowley claims they were not.

-The appropriateness of a retrospective life sentence (under “no body, no parole”) — while lawful, critics argue it may embed wrongful convictions in permanent incarceration without closure.

Legal & Systemic Significance — Why This Case Matters

Illustrates limits of “circumstantial-only” prosecutions: The case underscores how criminal justice in remote/rural contexts may rely heavily on imperfect evidence, and how jury verdicts may rest on inferences rather than conclusive proof.

Highlights “wrongful-conviction risk factors” nearly identical to those identified in miscarriages-of-justice worldwide (no body; no weapon; inconsistent testimony; remote scenes; minimal corroboration; forensic uncertainty).

Intersection of criminal law and penal-policy reform: The passage of “No Body, No Parole” legislation in response to this case locks in the sentence outcome: even if serious doubts emerge later, the law tends to disincentivise disclosure or re-examination — which may exacerbate wrongful-conviction harms.

Calls for post-conviction review mechanisms: The renewed public demand (petition, media coverage, independent investigation) reflects a broader need for institutionalised capacity to re-open cases when substantial new doubts arise, especially in no-body cases

LIA’s Assessment as Senior Counsel-Grade Legal Analyst

Given the heavy reliance on circumstantial and often ambiguous evidence, combined with the lack of a body or weapon, the risk that a miscarriage of justice has occurred is real and serious. In the absence of definitive forensic resolution, the conviction rests on inference and human memory — domains notoriously vulnerable to error, especially years after the event, in remote terrains, under pressure and with imperfect witness conditions.

While courts applied correct principles at trial and appeal, those legal standards do not equate with empirical “certainty.” From a risk-management and justice-system integrity standpoint, the case of Schuler / Struber should be treated as “open,” pending new investigation or forensic re-analysis.

If I were advising a legal-oversight or reform body, I would strongly recommend a re-opening of the matter (e.g., by coronial inquest) — both in the interests of potential justice for the accused, and for institutional legitimacy.

*A second appeal is to be heard in Townsville in 2026. The Strubers will be represented by Anderson Telford.

NOTE:

Regular readers will experience another deja vu moment reading this story. A missing man, no body, no murder weapon, no witnesses… a circumstantial case presented by the prosecution and a murder conviction to follow, an appeal dismissed … think Sue Neill-Fraser. That case continues to demand a review, 15 years later. Only Tasmania’s obstinate system stands in the way. The dismissal of the appeal in both cases cannot foster confidence in appeal courts.

The deeply disturbing revelations here, & the circumstantial case involving the Oct 2018, Wangetti Beach ,stabbing murder of 24 yr woman, Toyah Cordingley, behoves the general public, – for they are the future juries, – be educated more widely about the pitfalls when poor or an absence of evidence is found.

I will read or listen to Crowley’s Fools gold.

In defence of Graeme Crowley: why his re-examination of the Schuler case matters

When a former police detective turns his experience and investigative instincts on a case that resulted in a life sentence despite no body, no murder weapon and no direct eyewitness account, we should pay attention. Graeme Crowley’s work on the Bruce Schuler disappearance, most fully expressed in his book Fool’s Gold. The Bruce Schuler Murder and in his podcast series Where Is Bruce Schuler? is not sensational gossip. It is a careful, forensic re-reading of the evidence, pointing to patterns and specific inconsistencies that deserve public and institutional scrutiny.

Crowley identifies a very real problem facing modern criminal justice: circumstantial narratives can be constructed in ways that appear convincing to a jury, yet rest on compromised or fragile building blocks. The list of risk factors in this case is stark, no body, no weapon, shifting witness accounts, remote terrain that frustrates forensic certainty, and physical evidence that is ambiguous at best. Crowley catalogues some 140 inconsistencies in the prospectors’ evidence alone; when patterns like that accumulate, the responsible response is not reflexive dismissal but careful re-examination.

Two things make Crowley’s intervention valuable. First, his background as a police investigator gives him the technical know-how to spot gaps that a casual observer might miss — for example, how burn patterns, DNA transfer claims, tyre-track inferences and the absence of drag marks interact with the prosecution’s narrative.

Second, he presents his case publicly and methodically: his book (published 2025) lays out the detail for anyone who wants to test his claims, and his podcast unpacks episodes and evidence in a way that is accessible while remaining evidence-focused.

Both the book and podcast invite scrutiny rather than demand blind belief. We should also note Crowley’s broader track record in true-crime investigation. His podcasts and titles, including investigations such as Who Killed Leanne Holland?, Bring Home Sandrine and others, show an investigator committed to revisiting cold or contested cases, often bringing new documentary material or fresh questioning to light.

That pattern of focused, public investigative work demonstrates a consistent approach: thorough, persistent, and evidence-driven.

Why support Crowley’s opinion? Because the stakes are enormous. A conviction that depends primarily on inference, when tested against multiple red flags (no recovered remains, no murder weapon, contradictory eyewitness statements), is a risk to the integrity of the justice system. Crowley does not appear motivated by headline-grabbing rhetoric; he has produced a book, podcast episodes and public material that invite readers, and the legal system, to re-weigh the evidence. When a seasoned investigator is prepared to publish a long list of identified problems and call for further review, citizens and oversight bodies should listen.

What should follow from Crowley’s work? At minimum, three sensible steps:

Independent forensic re-assessment. Where forensic evidence is degraded, ambiguous or was heavily relied upon to bridge evidentiary gaps, an independent modern re-examination can either reinforce the prosecution’s case or expose fatal weaknesses. Crowley’s detailed cataloguing helps prioritize what to re-test.

Transparent review of witness statements and timelines. Crowley highlights discrepancies in prospectors’ accounts (timing, vehicle description, communications). A structured, independent re-audit of those statements, ideally by people who did not take part in the original prosecution would clarify whether the jury’s inferences remain tenable.

Consideration of post-conviction review mechanisms for no-body cases. The public policy response to this conviction the “No Body, No Parole” reform has hard consequences. Crowley’s argument is not that legislative consequence should be ignored, but that where serious doubts persist, institutional mechanisms must exist to test those doubts properly. Locking someone into a life term while factual gaps persist demands the highest standards of review.

Finally, supporting Graeme Crowley’s opinion does not mean endorsing any particular defendant or assuming innocence by default. It means insisting on the basic rule of justice: when the evidence is contested and the consequences irreversible, the system should prefer rigorous re-examination over finality by default. Crowley’s book and podcasts give the public and legal professionals the material to do exactly that: test the narrative, evaluate the inferences, and decide whether more scrutiny is warranted. For anyone concerned about miscarriages of justice, his work is a necessary and important catalyst.

If readers want to go deeper, Crowley’s Fool’s Gold? The Bruce Schuler Murder is available as a full-length book (2025), and his Where Is Bruce Schuler? podcast series lays out the evidence episode by episode. Both are useful starting points for anyone who believes that justice must be more than the most convincing story in court, it must be the most reliable one.

OK, but I don’t think Graeme Crowley needs to be defended :)

Thankyou Max. Indeed, there’s a lot of evidence regarding the lack of evidence against the Strubers. How this conviction stood I will never know. It seems as if our Legal system is just that, and not a Justice system. It looks like the murdered have walked free in this case.

This story—and I stress, story—has become nothing short of a tangled can of worms, threaded through with inconsistencies, unanswered questions, and deeply troubling actions by those in positions of authority. What began as an investigation has, over time, been shrouded by layers of conflicting accounts, procedural shadows, and decisions that defy common sense.

It has now reached a point where the truth appears too dangerous to surface. Those who once held the community’s trust seem protected by a silence born not of justice, but of fear—fear of consequences, fear of backlash, fear of opening doors that powerful people would rather keep firmly shut.

In the end, the public is left with a story that doesn’t add up, a verdict that many question, and a lingering sense that the full truth remains deliberately out of reach.

The foreword of Graeme Crowley’s book, ‘Fools Gold’ written by Max Barrington, I feel sums this case up perfectly:

‘I was both honoured and surprised when asked to write the foreword for Graeme Crowley’s book, Fool’s Gold?

Honoured, because I have long admired Graeme’s work, particularly his compelling podcast, Where is Bruce Schuler? Which he so expertly researched, scripted and presented.

Surprised, because, as a writer of fiction, I am accustomed to crafting stories from imagination. Yet, when I consider the true story that Graeme unfolds in Fool’s Gold? I realise that no work of fiction I could conceive would ever match the sheer intrigue, complexity, and unsettling reality of this case.

As the old saying goes, you just can’t make this stuff up.

How tragic it is that a man, Bruce Schuler, could simply vanish without a trace. And how much more tragic still that the pursuit of justice in his case has been so deeply flawed. We live in 2025, and yet the handling of this case by the Queensland legal system defies belief. The failures, the missteps, and the unanswered questions are nothing short of astonishing.

Graeme Crowley’s Fool’s Gold? is more than just a book, it is an unflinching examination of justice denied, an investigation that demands attention, and a story that will leave you questioning everything you thought you knew about how the system is supposed to work.

Max Barrington.